Hank Aaron, baseball’s one-time home run king, dies at 86

Published 2:31 pm Friday, January 22, 2021

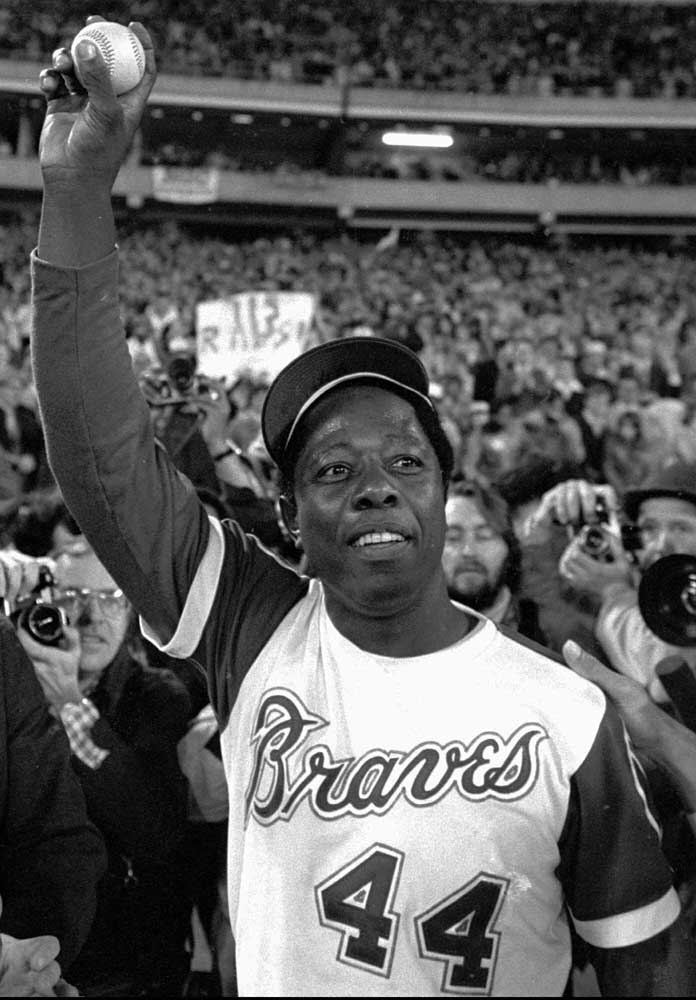

- Left: In this April 8, 1974, file photo, Atlanta Braves’ Hank Aaron holds aloft the ball he hit for his 715th career home in Atlanta. Hank Aaron, who endured racist threats with stoic dignity during his pursuit of Babe Ruth but went on to break the career home run record in the pre-steroids era, died early Friday. He was 86. Right: Aaron waves to the crowd during Baseball Hall of Fame induction ceremonies in Cooperstown, N.Y., in this July 28, 2013, file photo.

ATLANTA — Hank Aaron, who endured racist threats with stoic dignity during his pursuit of Babe Ruth’s home run record and gracefully left his mark with 755 homers and a legacy as one of baseball’s greatest all-around players, died Friday. He was 86.

The Atlanta Braves, Aaron’s longtime team, said he died peacefully in his sleep. No cause was given.

Trending

Aaron made his last public appearance just 2 1/2 weeks ago, when he received the COVID-19 vaccine. He said he wanted to help spread the word to Black Americans that the vaccine was safe.

“I feel quite proud of myself for doing something like this,” he said. “It’s just a small thing that can help zillions of people in this country.”

“Hammerin’ Hank” set a wide array of career hitting records during a 23-year career spent mostly with the Milwaukee and Atlanta Braves, including RBIs, extra-base hits and total bases.

But the Hall of Famer will be remembered for one swing above all others, the one that made him baseball’s home-run king.

It was a title he would be hold for more than 33 years, a period in which the Hammer slowly but surely claimed his rightful place as one of America’s most iconic sporting figures, a true national treasure worthy of mention in the same breath with Ruth or Ali or Jordan.

Hank Aaron’s survivors include his wife, Billye (Palestine native and Texas College graduate), and their daughter, Ceci. He also had four children from his first marriage to Barbara Lucas — Gail, Hank Jr., Lary and Dorinda.

Trending

Former presidents quickly weighed in with condolences.

“One of the greatest baseball players of all time, he has been a personal hero to us,” said Jimmy Carter, speaking for himself and former first lady Rosalynn Carter, a couple who often attended Braves games. “A breaker of records and racial barriers, his remarkable legacy will continue to inspire countless athletes and admirers for generations to come.”

George W. Bush, a one-time owner of the Texas Rangers, presented Aaron in 2002 with the Presidential Medal of Freedom — the nation’s highest civilian honor.

“The former Home Run King wasn’t handed his throne,’” Bush said in a statement Friday. “He grew up poor and faced racism as he worked to become one of the greatest baseball players of all time. Hank never let the hatred he faced consume him.”

Aaron’s death follows that of seven other baseball Hall of Famers in 2020 and two more — Tommy Lasorda and Don Sutton — already this year.

“He was a true Hall of Famer in every way,” said former baseball Commissioner Bud Selig, a longtime friend. “His contributions to the game and his standing in the game will never be forgotten.”

On April 8, 1974, before a sellout crowd at Atlanta Stadium and a national television audience, Aaron broke Ruth’s home run record with No. 715 off Al Downing of the Los Angeles Dodgers.

Aaron finished his career with 755, a total surpassed by Barry Bonds in 2007 — though many continued to call the Hammer the true home run king because of allegations that Bonds used performance-enhancing drugs.

Bonds finished his tarnished career with 762, though Aaron never begrudged someone eclipsing his mark.

His common refrain: More than three decades as the king was long enough. It was time for someone else to hold the crown.

Besides, no one could take away his legacy.

“I just tried to play the game the way it was supposed to be played,” Aaron said, summing it up better than anyone.

He wasn’t on hand when Bonds hit No. 756, but he did tape a congratulatory message that was shown on the video board in San Francisco shortly after the new record-holder went deep. While saddened by claims of rampant steroid use in baseball in the late 1990s and early 2000s, Aaron never challenged those marks set by players who may have taken pharmaceutical shortcuts.

“Thank you for everything you ever taught us, for being a trailblazer through adversity and setting an example for all of us African American ballplayers who came after you,” Bonds said. “Being able to grow up and have the idols and role models I did, help shape me for a future I could have never dreamed of.”

Even though Bonds claimed the home run record, Aaron always had that April night in 1974, a welcome diversion at the time for a country mired in the Watergate scandal.

“Downing was more of a finesse pitcher,” Aaron remembered shortly before the 30th anniversary of the landmark homer. “I guess he was trying to throw me a screwball or something. Whatever it was, I got enough of it.”

Aaron’s journey to that memorable homer was hardly pleasant. He was the target of extensive hate mail as he closed in on Ruth’s cherished record of 714, much of it sparked by the fact Ruth was white and Aaron was Black.

“If I was white, all America would be proud of me,” Aaron said almost a year before he passed Ruth. “But I am Black.”

Aaron was shadowed constantly by bodyguards and forced to distance himself from teammates. He kept all those hateful letters, a bitter reminder of the abuse he endured and never forgot.

“It’s very offensive,” he once said. “They call me ‘(n-word)’ and every other bad word you can come up with. You can’t ignore them. They are here. But this is just the way things are for Black people in America. It’s something you battle all of your life.”

After retiring in 1976, Aaron became a revered, almost mythical figure, even though he never pursued the spotlight. He was thrilled when the U.S. elected its first African American president, Barack Obama, in 2008. Former President Bill Clinton credited Aaron with helping carve a path of racial tolerance that made Obama’s victory possible.

“We’re a different country now,” Clinton said at a 75th birthday celebration for Aaron. “You’ve given us far more than we’ll ever give you.”

Aaron spent 21 of his 23 seasons with the Braves, first in Milwaukee, then in Atlanta after the franchise moved to the Deep South in 1966. He finished his career back in Milwaukee, traded to the Brewers after the 1974 season when he refused to take a front-office job that would have required a big pay cut.

While knocking the ball over the fence became his signature accomplishment, the Hammer was hardly a one-dimensional star. In fact, he never hit more than 47 homers in a season (though he did have eight years with at least 40 dingers).

But it can be argued that no one was so good, for so long, at so many facets of the national pastime.

The long ball was only part of his arsenal.

Aaron was a true five-tool star.

He posted 14 seasons with a .300 average — the last of them at age 39 — and claimed two National League batting titles. He finished with a career average of .305.

Aaron also was a gifted outfielder with a powerful arm, something often overlooked because of a smooth, effortless stride that his critics —with undoubtedly racist overtones — mistook for nonchalance. He was a three-time Gold Glove winner.

Then there was his work on the basepaths. Aaron posted seven seasons with more than 20 stolen bases, including a career-best of 31 in 1963 when he became only the third member of the 30-30 club — players who have totaled at least 30 homers and 30 steals in a season.

To that point, the feat had only been accomplished by Ken Williams (1922) and Willie Mays (1956 and ‘57).

Six feet tall and listed at 180 pounds during the prime of his career, Aaron was hardly an imposing player physically. But he was blessed with powerful wrists that made him one of the game’s most feared hitters.

Aaron hit 733 homers with the Braves, the last in his final plate appearance with the team, a drive down the left field line off Cincinnati’s Rawley Eastwick on Oct. 2, 1974. Exactly one month later, he was dealt to the Brewers for outfielder Dave May and minor league pitcher Roger Alexander.

Aaron was elected to Cooperstown in 1982, his first year of eligibility and just nine votes short of being the first unanimous choice ever to the Baseball Hall of Fame.

In 1999, baseball began honoring its top hitter with the Hank Aaron Award, akin to the Cy Young for pitchers. Three years later, a nationwide vote named Aaron’s No. 715 as the second-most memorable moment in baseball history, eclipsed only by Cal Ripken Jr. breaking Lou Gehrig’s record for consecutive games played.

“He might be the greatest player of all time,” said the late Tony Gwynn, a fellow Hall of Famer. “Just look at his numbers. Everybody characterizes him as a home run hitter because he’s held that record so long. But he was a great baserunner, a great defender, a great player period.”