Hows and whys of pond fertilization

Published 10:20 am Monday, March 7, 2016

Few pond management practices are as misunderstood and misapplied as fertilization. Why, when, how and with what material seem to be vague in the minds of many pondowners.

Let’s start with why we fertilize farm ponds. Phytoplankton (single-celled algae) form the base of the aquatic food chain or web. If we can ramp up the production of phytoplankton at the base of the chain/web, it stands to reason that we should then be able to increase the production of critters at the upper levels of the chain or web, which we often refer to as sportfish.

Trending

Production of phytoplankton requires nutrients, which are largely supplied by organic matter entering the pond from the watershed and/or through the natural breakdown of organic matter in the pond itself. Like all green plants, phytoplankton equire nitrogen, phosphorous and potassium (N-P-K) from these sources to grow.

Boosting phytoplankton increases the zooplankton population, the microscopic animals fed on by some invertebrates and larval/small fish. These are then fed on by larger fish that are predacious and perhaps an additional trophic level would increase to the top tier predators present in your pond, including but not necessarily limited to largemouth bass.

The when of fertilization varies across the great state of Texas due to latitude and vastly differing climatic conditions. In far south Texas, ponds may reach 65 to 70 degrees F near the water’s surface by March 1, however ponds near Dalhart may not reach this same temperature until mid to late April.

It’s important to note that this is just the start of the fertilization process. Reduced rate applications will be needed as follow-up which in the form of another 2 to 4 applications (depending on weather conditions and the pond’s inherent productivity) until waters cool in September/October and fertilization is ceased for the year.

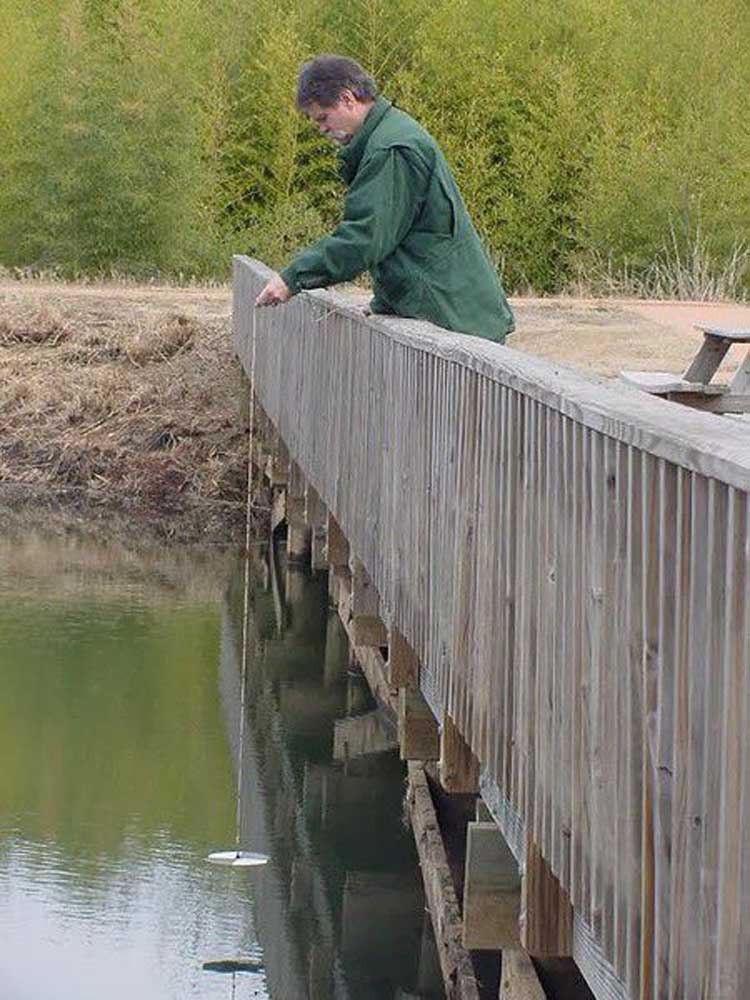

The pondowner must learn to “read” the water. The idea is to maintain a light greenish color to the water (indicative of a phytoplankton bloom). Anytime the water begins to clear and allow visibility of more than 18 inches using a Seechi disk (see photo), it’s time for that next reduced rate application that is typically at half the rate of the initial application.

The how of pond fertilization depends on the product used. When I became a practicing fisheries biologist almost 40 years ago, the only option was to use granular fertilizer similar to what is used on lawns or pastures. The preferred fertilizer blends were 16-6-4 or 20-20-5 applied at initial rates of 100 and 80 pounds per surface acre of water, respectively.

Trending

Thankfully, liquid pond fertilizers came on the market and in the late 1970’s and early 1980’s so this eased the application process. Two gallons per surface acre of a 10-32-0 or 12-34-0 proved to provide quicker results with less labor than the old granulars, with reduced rates of one gallon per surface acre applied as needed to maintain the bloom.

The liquid fertilizers are heavier than water, therefore pouring them straight into the water column means they will sink to the bottom, which could limit their availability. By mixing several parts of water with each part fertilizer in buckets and pouring the solution into the propwash of an outboard motor, pondowners found that the time spent fertilizing the water could be drastically reduced.

More recently, fertilizers packaged as water soluble powders became available for pondowners to use. These products typically have an analysis of 10-52-4 or equivalent and should be applied at the rate of 6 to 10 pounds per surface acre. Simply open the bag and pour in the prescribed amount of fertilizer based on surface acreage and it dissolves and becomes immediately available to plant life.

Sounds simple enough, right? Well, there is a long list of caveats that go into making your final decision to fertilize or not to fertilize.

The ideal scenario would be to fertilize a larger pond (greater than one surface acre) that is being managed for sportfish production (e.g., largemouth bass). But first, ask yourself, “Do I really need to produce more fish?”

So which ponds and under what conditions should one choose to skip the fertilization process? To start with, consider your commitment-If you do not plan to make the reduced rate applications required to maintain the bloom throughout the growing season or do not plan to continue in subsequent years, then don’t start a fertility program at all.

Do not fertilize a muddy pond. If there is no sunlight penetration into the water column to 12 to 15 inches, then it is doubtful that the phytoplankton can adequately bloom in response to the nutrients provided.

Likewise, do not fertilize a pond that has constant or steady water exchange. It is difficult to establish a bloom if the nutrients continually leave via the spillway. However, if the excess flow is being channeled through a bottom release drainpipe, then a fertility program may be applicable.

Lastly, do not fertilize a pond that already has aquatic vegetation present and actively growing. These plants will compete and often successfully outcompete phytoplankton for the nutrients and could make a weed problem worse. It should be pointed out however, that if the bloom is established and maintained before weeds begin to grow, the likelihood of submergent weed problems is decreased because the bloom blocks sunlight from the pond bottom.

Done correctly, a fertilization program is a cost-effective method to greatly increase fish populations if an intensive management strategy is in place. However, as the number of mouths to feed increases, more aggressive fish harvest may be a necessity as your largemouth bass, bluegill and channel catfish respond to the increased buffet created for them.

Contact Dr. Billy Higginbotham at Billy.Higginbotham@ag.tamu.edu.