Coyotes can be both good and bad for Texas wildlife

Published 7:44 pm Saturday, October 11, 2014

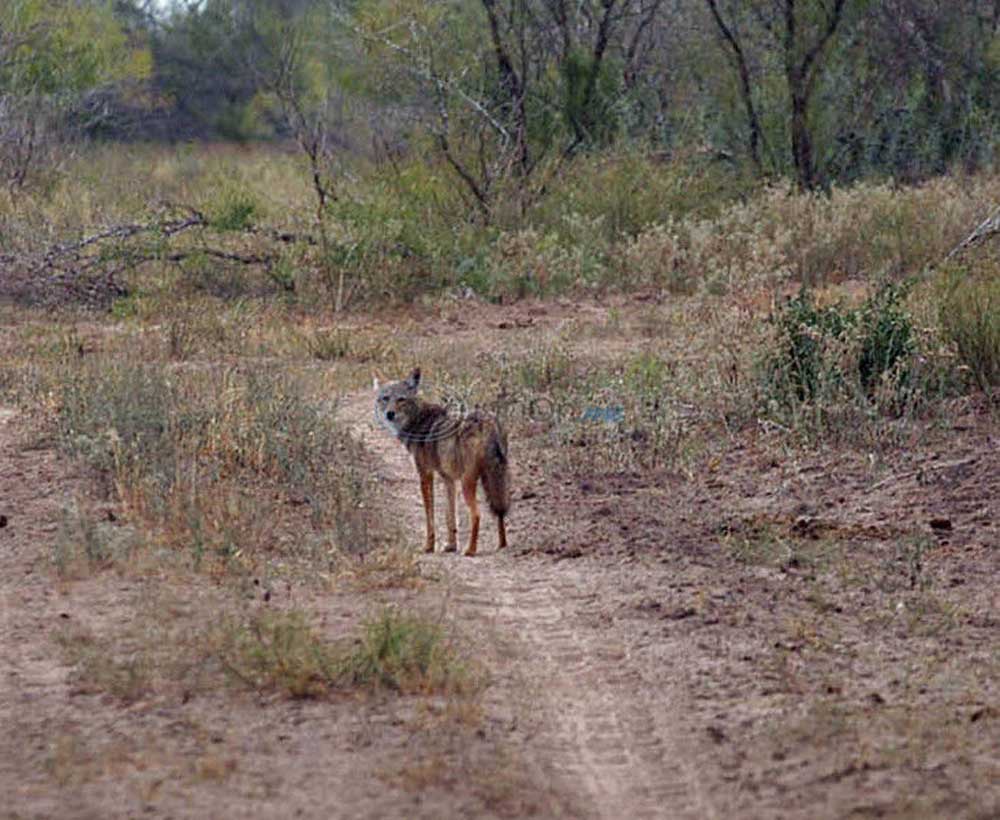

- Mike Leggett/11-15-11/AMERICAN-STATESMAN/A lone coyote stands at the edge of the brush, checking out his hunting area for the day.

The lonesome cry of a coyote is as much about the lore of Texas as the cattle drives up the Chisholm Trail.

While pushing cattle from horseback are today reserved only for old movie and books, coyotes continue to thrive not only in rural areas, but within the boundaries of Texas’ largest cities.

Without a greater predator, coyotes are at the top of the food chain in Texas. A non-game species, coyotes were at one time highly sought after by trappers who received a good payday for their hides, but that market disappeared with the declining interest in fur.

There is little pressure on coyotes today. In the western portion of the state coyotes are still controlled by ranchers who blame them for losses of sheep, goats and young calves.

Hunters also randomly hunt coyotes, some participating in the long-time practice of varmint calling. Others are convinced that wildlife and coyotes cannot coexist on the same range.

To that point the truth, as the saying goes, lays somewhere in between.

Wildlife experts across Texas describe coyotes as at times troublesome, but certainly not the biggest problem facing any of the state’s wildlife species.

Alan Cain, Texas Parks and Wildlife Department’s white-tailed deer program leader said, for example, there are individual instances where coyotes may be an issue with a deer herd, but that isn’t the case across the state.

“From a statewide perspective coyotes are not an issue. We have too many deer as it is. On localized places where density is real low and you have low fawn recruitment, yeah, short-time coyote control may be necessary. They will take a deer or two, but they are not going to expend that much energy to take down a buck or doe. If you have a coyote problem then you probably have a bigger issue,” Cain explained.

There are states in the Southeast that believe coyotes are impacting their deer populations, but he said in those cases the states are just now seeing coyotes for the first time. Cain said states like Georgia and South Carolina have low fawn density, but they also have fairly liberal bag limits based on the size of their herd. He believes in both cases the states would be better served by tighten limits than worrying about predators.

The biologist said he knows many landowners who use coyotes to their advantage in keeping deer numbers down, something that can’t always be done on large acreage simply by hunting.

Cain said one argument he hears for taking coyotes is that they aren’t selective about what bucks they attack, potentially taking a young one that could grow into a trophy.

“In reality that philosophy doesn’t hold up very well. Also, keep in mind if someone were to try to remove coyotes to benefit the deer herd they would have to remove coyotes over a fairly large area, thousands of acres, to really make a difference,” Cain said. He added large-scale predator control can lead to a short-term void that could eventually be filled by even more coyotes.

Cain said an exception could be small-acreage, high-fenced properties with smaller herds and less space for the deer to escape to.

“If someone was going to try to control coyotes or have to do it, I would do it in March and April and continue through July when fawns are most vulnerable,” Cain said.

In recent years quail researcher Dr. Dale Rollins has held predator appreciation days across North and Central Texas. He wants landowners and hunters to know they can make matters worse if they mess with the balance of nature.

“We’ve done some studies on coyotes at the Rolling Plains Quail Research Ranch, and to some degree the results are contradictory, or maybe just illustrating the complexity inherent therein,” Rollins said.

He said one three-year study looked at the diet of coyotes. Out of the 1,028 scat samples examined, there was evidence of a quail in just one. The remainder was skunks, raccoons, feral hogs and even a badger.

He said a companion study on raccoons tagged with GPS collars showed coyotes tended to keep raccoons, especially females with kits in the brush and away from nest sites.

“That research supported my contention that there are much worse predators of quail than coyotes, and that coyotes did indeed work on some of them,” Rollins said.

However, Rollins added that 30 to 50 percent of quail nests are lost each summer, and that coyotes are a common predator.

He added that coyote numbers on the RPQRR near Roby are high, and that management efforts to reduce their numbers will be conducted next year.

“If RPQRR was a deer research ranch I’d have already worked on the coyotes via aerial gunning in March to improve fawn survival, as we have a low deer density. But it’s not, and I don’t mind the coyotes taking the pressure off the cooker,” he said.

Where hunters, especially in East Texas, may be shooting themselves in the foot by eliminating coyotes is in controlling wild pigs.

“I believe that the coyote population in East Texas has positively responded to the increase in pig populations over the past three decades,” said Dr. Billy Higginbotham, Texas AgriLife Wildlife Specialist. “Small pigs make ideal food items and there are places in the area river bottoms like the Neches that it is difficult to find coyote scat that does not contain pig hair. Again, the predation level is certainly not sufficient to control the pig population, but they are apparently using the young pigs as a food source extensively.”

Higginbotham added, as do other wildlife biologists, that the random removal of coyotes has little to no impact on their numbers.

Have a comment or opinion on this? Email Steve Knight at outdoor@tylerpaper.com, follow him on Facebook at TylerPaper Outdoors and on Twitter @tyleroutdoor.