Texas vs. NAACP records found

Published 10:53 pm Sunday, June 21, 2015

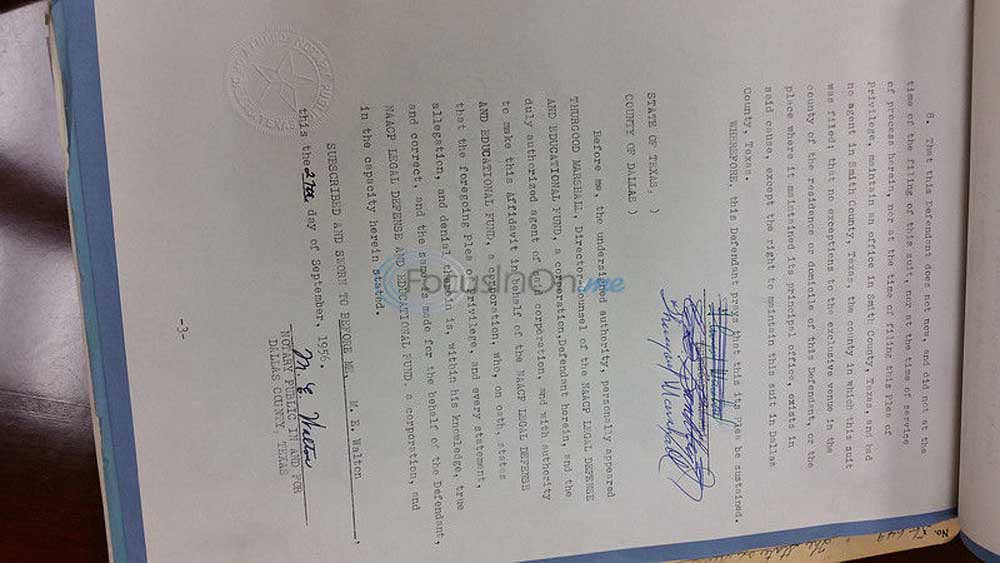

- The signature of former Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall appears on this document from a trial he litigated in Smith County in 1956-57 (Smith County Courthouse)

Former Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall had just come off an incredible victory that changed the nation when he was called to Tyler for help dealing with the aftermath of Brown v. Board of Education.

After the Supreme Court of the United States’ ruling that “separate educational facilities are inherently unequal,” some southern states attempted to sue the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People out of existence. At the time, the NAACP was the primary driving force behind ending segregation. It’s legal division, which was considered a separate entity helped file lawsuits and pay for the subsequent litigation.

Recently, the Smith County Courthouse announced they had uncovered documents from the state of Texas’ case against the NAACP, which was tried in Tyler.

The documents run through the trial, which began in 1956, and end during the appeal process.

In the documents, the state accused the NAACP of practicing barratry, meaning they allegedly filed a large number of meritless lawsuits.

The lawsuits in question, more than 50, were almost all filed against colleges or school districts violating integration rulings. The earliest lawsuit named was filed in 1951 and dealt with segregation at Tyler State Park.

The state also said the NAACP had no right to practice law in Texas, as it was a not for profit corporation formed under New York state laws.

The trial and subsequent appeal were lengthy, spanning nearly two years. At the same time, the state of Arkansas was pursuing similar litigation, hoping to handicap the NAACP.

At the time, the hotels in Tyler did not rent to black people so Marshall and the rest of the NAACP legal counsel was forced to drive back and forth to Dallas daily. The attorney general’s office was given free rooms and meals at the Blackstone Hotel, just a block away from the courthouse, according to historian Michael Gillette’s dissertation “The NAACP in Texas, 1937-1957.”

NAACP Executive Secretary Roy Wilkins was called to testify after the state accused the association in engaging in political activity.

Wilkins said the NAACP had “an inescapable duty to accelerate the process of democracy and to demolish the whole Jim Crow structure.” He also recognized that the association’s policy forbade endorsement of political parties or candidates.

On October 23, 1956, Judge Otis T. Dunagan would rule the NAACP was a foreign corporation doing business in Texas illegally, without a permit. The judge indicated he believed the NAACP was attempting to make a profit. An injunction was issued, leaving only the Dallas regional office able to operate. Even then, it could not engage in activities in Texas.

Having lost the case, the NAACP in Texas was shut down for all intents and purposes. The attorney general took his time setting up a second trial.

When the second trial convened on December 3, 1956, the NAACP requested a change of venue to Austin or Dallas. The state argued they had no right to request where they would be tried, since they were a foreign corporation.

During this time, Marshall was unsuccessfully working on a compromise with the attorney general and the state. By April of 1957, a new attorney general, Will Wilson. had been sworn in. Marshall found Wilson was far more interested in a compromise than his predecessor.

Wilson agreed not to revoke the NAACP’s charter or challenge its nonprofit status, allowing them to continue operation in Texas. The association agreed not to violate barratry laws, pay franchise taxes and comply with state laws.

The agreement placed severe restrictions on the association, charging them with only performing activities deemed educational or charitable.

Marshall then urged the association not to appeal the case. The board of directors decided to appeal, believing that leaving the ruling standing would allow future cases in other states and remove their ability to help blacks secure rights through the court, as they had done for the past 40 years.

The result was a permanent injunction against the NAACP practicing law in Texas, but Marshall’s compromise was honored.

This left the NAACP handicapped at the beginning of the civil rights movement. Many states had filed similar suits and legislatures, including Texas, passed laws further restricting the association.

The NAACP sustained a devastating blow in Smith County, but Marshall ensured the association did not fold completely. In the years to come, the NAACP would be instrumental in the push to end segregation and ensure equality.