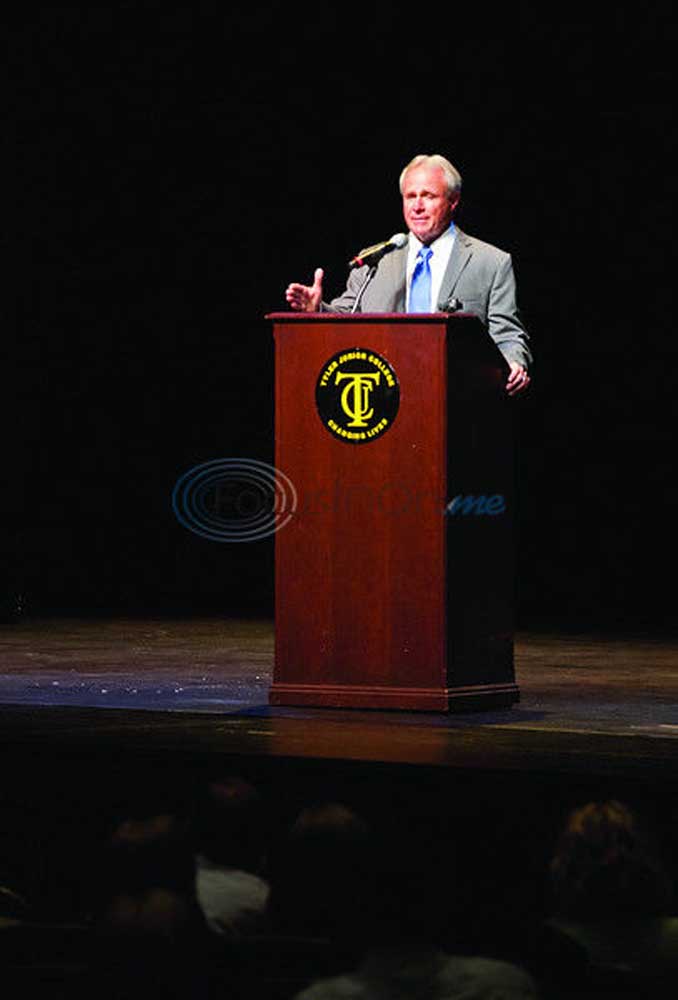

Michael Morton tells captivated student audience of the 24 years he was wrongly imprisoned

Published 6:38 pm Wednesday, September 30, 2015

- Michael Morton speaks during the Smith County Bar Association's Constitution Day public event at Tyler Junior College Wednesday. Morton was convicted by a Texas court in 1987 for the murder of his wife and after 25 years was found innocent. (Sarah A. Miller/Tyler Morning Telegraph)

Throughout his 25-year ordeal, Michael Morton says he never lost his faith in the criminal justice system – or the Constitution. In 1987, Morton was wrongly convicted of murdering his wife. He spent nearly a quarter of a century in the penitentiary, until DNA evidence exonerated him.

“I knew if I was ever going to get out, it would be because of this document – the Constitution,” Morton told an auditorium filled with Tyler-area students, all participating in the Smith County Bar Foundation’s Constitution Day observance.

“I’m here today because I’m you,” Morton said. “Or at least, I used to be. I used to be a really average guy. I was living in Austin. I was married, we had a child. We were working hard, but we were where we wanted to be, doing what we were supposed to be doing.”

That changed on Aug. 13, 1986, when Morton’s wife was beaten to death in the couple’s bed. The Williamson County Sheriff’s Office quickly settled on Morton as the sole suspect.

He was arrested a few weeks later. He was 31.

“I went to the door, with my 3-year-old son on my hip,” he told the rapt teenagers in Tyler Junior College’s Wise Auditorium. “It was the sheriff; he’d come to arrest me. As all of these terrible things were happening in my life, the worst was seeing my son as they put handcuffs on me.”

At that moment, he realized his life would never be the same, he said.

“When you’re put in the back of a police car, your perspective changes,” Morton said. “You change. I had never been arrested before. I had no police record. So for the first time, I understood the weight and the strength of the state – of the government.”

He was arrested in September of 1986; the trial took place in February of 1987. Even as the trial progressed, Morton said, his attorneys “smelled a rat.” Some things didn’t add up. Morton’s lawyers wondered if there was evidence the prosecution wasn’t turning over to the defense.

When the judge read the guilty verdict, Morton said, it somehow felt unreal.

“It was like hearing a foreign language – a foreign language you understand,” he said. “When the state takes your liberty, you lose a lot. I lost my son. I lost my freedom. I lost my reputation.”

The trial and subsequent appeals proved very costly.

“So I lost all my money,” he said. “When you’re in that situation, you spend every dime. And after I spent all my money, my parents spent all of theirs.”

And he lost his friends, he added.

“Most people just feel that where there’s smoke, there’s fire,” Morton explained.

When he entered prison, he said, he was an angry man. And the harsh environment just made it worse.

“Prison is dehumanizing,” Morton said. “It’s gray. It’s monotonous. It’s soul-killing – and that’s not hyperbole. You lose who you are. I was 445494. Because in prison, without a number, you don’t exist. It changes who you think you are.”

The thought of his son, and his hope of one day reuniting with him, kept him going, Morton explained.

“Before I had my son, I was the center of my own universe,” he said. “Having a child changes that. It’s no longer all about you. That’s true of me when I was ‘inside.’ My son was the reason I wanted to get out. He was the reason I didn’t hang myself in my jail cell.”

Yet Morton acknowledges that in his bitterness, he actually began to plan his revenge. He devised means and methods of killing those he held responsible for the unjust verdict.

“I had been wronged, and I had a pretty good idea of by who,” he said. “I spent years planning how I would kill them.”

But something changed him. It was 2001, and he received a letter informing him that his son (now 18) was changing his name, and was to be adopted by the family that had raised him.

“Nothing had broken me,” Morton said. “My wife’s murder, my trial, prison – I wasn’t broken by those. But this broke me.”

He describes that brokenness as “a kind of bankruptcy.”

“I cried out to God,” he said. “I had nothing.”

Morton described a profound experience he had in his prison cell after he called upon God – it was God’s answer, he said.

“The reason I know it was real is that it changed me,” he said. “I wanted different things. I didn’t want revenge. I wanted to be worthy.”

Morton knew his first task was to forgive his enemies. That took time, and work, but when he did so, he said, “I felt lighter. Renewed. Cleansed.”

That wasn’t the end of his legal troubles, however. He would spend another decade in prison before being exonerated.

The way that happened, he told his audience, was through the diligence of his attorneys and the New York City-based Innocence Project. After years of appeals and requests to test evidence for DNA or other clues, a judge granted permission to have a bandana tested. It was found the day after Morton’s wife was murdered, but it was never brought up in court.

“The bandana had her DNA on it,” Morton explained. “And it was comingled with a man’s DNA – but it wasn’t mine.”

In fact, that DNA was already in the database. It belonged to a man named Mark Norwood, a convicted felon from California who was living in Texas at the time. Norwood since has been convicted of the murder of Christine Morton and he’s a suspect in the death of another woman.

The most frustrating aspect of the appeals process was that the Williamson County district attorney “fought us the whole way,” Morton said. That’s because the former district attorney, Ken Anderson, had gone on to become a state district judge in the county. So the new DA had little motivation to overturn the case – he had to practice in Anderson’s courtroom.

But Bexar County District Judge Sid Harle ordered that Morton be released on Oct. 4, 2011.

Later, a court of inquiry formally charged Anderson with prosecutorial misconduct. He was removed from the bench, and as part of his plea agreement, gave up his law license.

“The point is that evidence had been suppressed,” Morton explained. “We asked if there was any more evidence, and this district attorney said no, there’s nothing more. This was the rat my lawyers had smelled in 1986. When I was released, I had served exactly 24 years and seven months.”

Morton, 61, has since reconnected with his son, and even gotten married again, to a Kilgore woman.

He lent his name to the Michael Morton Act, a Texas law passed in 2013 that guarantees a more open discovery process in legal proceedings. And it says that prosecutors who are found to have suppressed exculpatory evidence can be jailed for up to 15 years.

“That means they won’t risk their freedom on the ‘iffy’ cases,” Morton said. “If they’re tempted to do the wrong thing for the right reasons, they’ll think twice.”

During a question-and-answer session following his speech, Morton brought the discussion back around to the Constitution.

“If, God forbid, something like this happens to you, the Constitution will protect you,” he told the students in attendance. “It will ensure you receive what’s due to you.”

Twitter: @tmt_roy