Amish veteran served despite religious beliefs

Published 11:23 pm Saturday, July 20, 2013

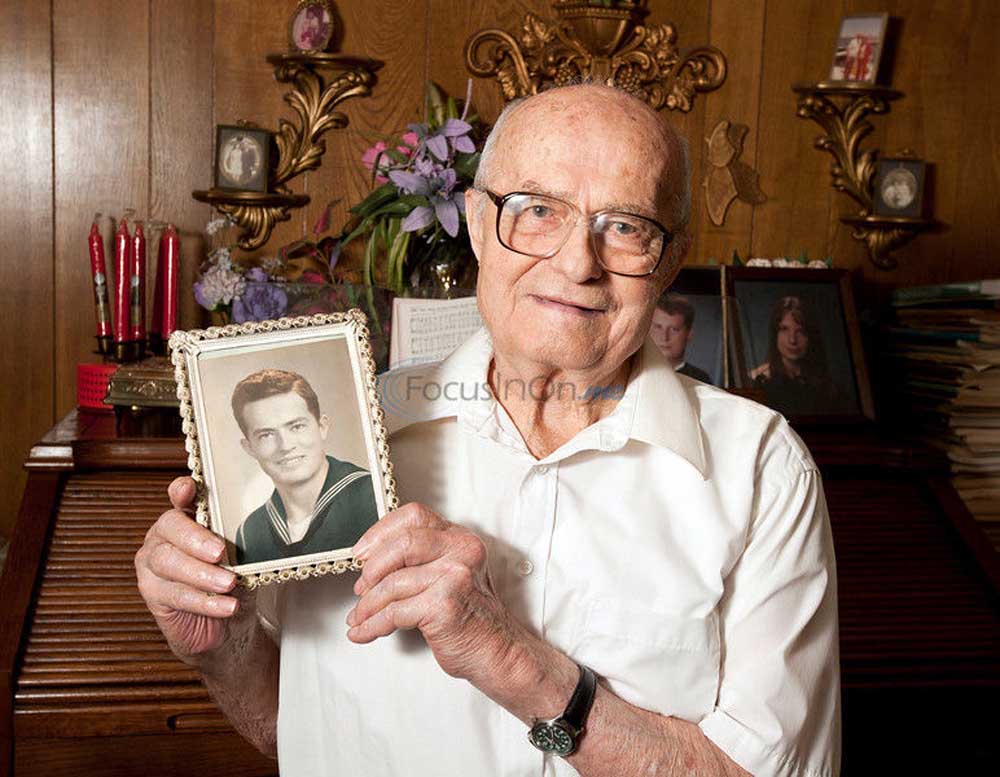

- photo by Sarah A. Miller/Tyler Morning Telegraph Tyler resident Floyd Helmeth was drafted into the United States Navy at age 18 during World War II. He was one of ten men to first see Nagasaki, Japan after the bomb was dropped.

Editors Note: Floyd Helmuth, of Tyler, the World War II veteran featured in this story, died June 25, shortly after being interviewed for this story. To honor his memory, his family has graciously agreed to allow his story to be told as part of an occasional series of profiles of World War II veterans in East Texas.

For one 18-year-old entering World War II, sailing to foreign waters wasn’t the only thing foreign to him.

Originally from Illinois, Floyd Helmuth was raised Amish before entering the war. He had never known the things many Americans view as necessities, or even luxuries.

The Amish “didn’t believe in going to war,” Helmuth said. “But I got drafted, and they gave me a choice of either Army or Navy, and I chose Navy.”

Helmuth could have declared himself a conscientious objector in 1944 when his draft notice came, but he didn’t.

As World War II developed, Congress — for the first time in its history — recognized the objector status as a legitimate moral stand. Before he could join the armed forces abroad toward the end of the war, Helmuth had to learn the simplicities of life during boot camp.

My family “didn’t believe in sending me to high school, and we didn’t have electricity,” he said. “When I was at boot camp, they had a company class that showed me how to use a telephone, and of all the people they chose to do a demonstration, they chose me. I’d never used a telephone in my life.”

“The man said, ‘Where you from?’ and I never forgot that,” he said laughing.

Helmuth spent three months in boot camp in Michigan before training for about four weeks in Florida as an engineer.

“They sent us to Portland, Ore., to get our ships,” he said. “That was the best train ride I ever had, from Fort Pierce, Fla., to Portland, Ore.”

Helmuth was then sent to the South Pacific in mid-1945 to take part in the largest amphibious assaults in the Pacific during World War II: the Battle of Okinawa, code-named Operation Iceberg.

Helmuth was made a helmsman for LCSL 104, a landing craft support boat, which carried a crew of 70 sailors. He worked around the clock — four hours at the helm, then four hours off.

“I was driving a ship before I was driving a car,” he said. “I drove a horse and buggy. It’s a different world.”

When Helmuth wasn’t at the helm, he was stationed on a 20-mm gun.

“Every other bullet was a tracer, and you could trace it straight to the target,” Helmuth explained about his time spent shooting the guns.

Helmuth’s boat’s duty was to lay a smoke screen on the harbor to prevent Japanese kamikaze attacks, he said. The suicide pilots would pick a ship and then try to destroy it by flying into it.

He, along with the rest of the 5th Fleet, was only 90 miles from the Japanese coastline.

The smoke ginny that produced smoke “was in the back of the ship, so we’d just go around the whole harbor laying a thick smoke.”

“Our radar could pick up on (the planes) immediately, so we would lay that screen,” he said. “It saved a lot of ships. I bet there were 100 Navy ships, aircraft carriers and destroyers” out in the harbor.

“We were there for 30 days, and it was 30 days of pure hell. The kamikazes, or suicide planes, came over at 2 a.m. every morning. You could almost set your clock by it. We were told not to shoot at them because our planes were up there, too.”

Very seldom did the planes come in daylight, he said, adding that they usually came in sets of three.

The closest call, Helmuth said, was one time as the sun was setting, a plane skimming the water wasn’t picked up on radar, he said.

“It was coming directly toward our ship,” he said. “I said, ‘That’s not one of our planes, that’s a … Zero.'”

As soon as the kamikaze rose up, it flew over Helmuth’s ship and went right into the side of an American destroyer anchored only 90 yards away, he said.

“It exploded in the mess hall. It was the largest destroyer,” he said. “It didn’t sink, but it did lots of damage and killed a lot of men because they were eating in the mess hall. They didn’t even know that any kamikazes were around. That was the biggest mess that I’d ever seen.”

Helmuth said at this point in the war, Japan was desperate, so desperate that suicide planes were constant, he added.

The Americans then dropped the first atomic bomb on Hiroshima about three months after the Okinawa battle ended, and Helmuth and his landing craft boat were to head to the Philippines.

Then the second atomic bomb was dropped on Nagasaki.

“We were only 50 miles away” when the second bomb dropped, he said. “We heard it on the radio, what they did; we weren’t even looking for it.”

Three or four days after the Japanese empire surrendered in September 1945, Helmuth and nine of his crewmates were told to go ashore in Nagasaki.

“The biggest thing I remember is we were walking through the debris, when a bunch of Japanese boys about 11 or 12 years old came out yelling, “Ohayou, Ohayou.’ We didn’t know what it meant, but it meant hello,” Helmuth said. “They were wearing Japanese Army uniforms. They were getting pretty desperate at that time, sending kids (into war).

“(Nagasaki) looked like a dozen tornadoes had gone through,” he said. “Bodies were still floating in the harbor. It wasn’t a pretty sight.”

The Navy didn’t consider the possibility of radiation poisoning when Helmuth and his fellow sailors were sent into the town, he said.

“We just walked in there, that was right after they officially surrendered,” he said. “I guess they sent us in to see if they were going to shoot us.”

After the war ended, Helmuth and his ship sailed to different ports before being sent home, where he eventually settled in Tyler.

In civilian life, Helmuth worked as a rancher, for Southland Distribution and for Tyler Foam Co. The former sailor, a member of the Cross Brand Cowboy Church in Tyler, was 88 when he died.

“Going into the Navy was a completely different world,” he said in early June. “I look at it this way, the Lord had a purpose.”-=