Lean’s 1970 film stumbles with unsympathetic characters

Published 10:23 pm Tuesday, June 11, 2013

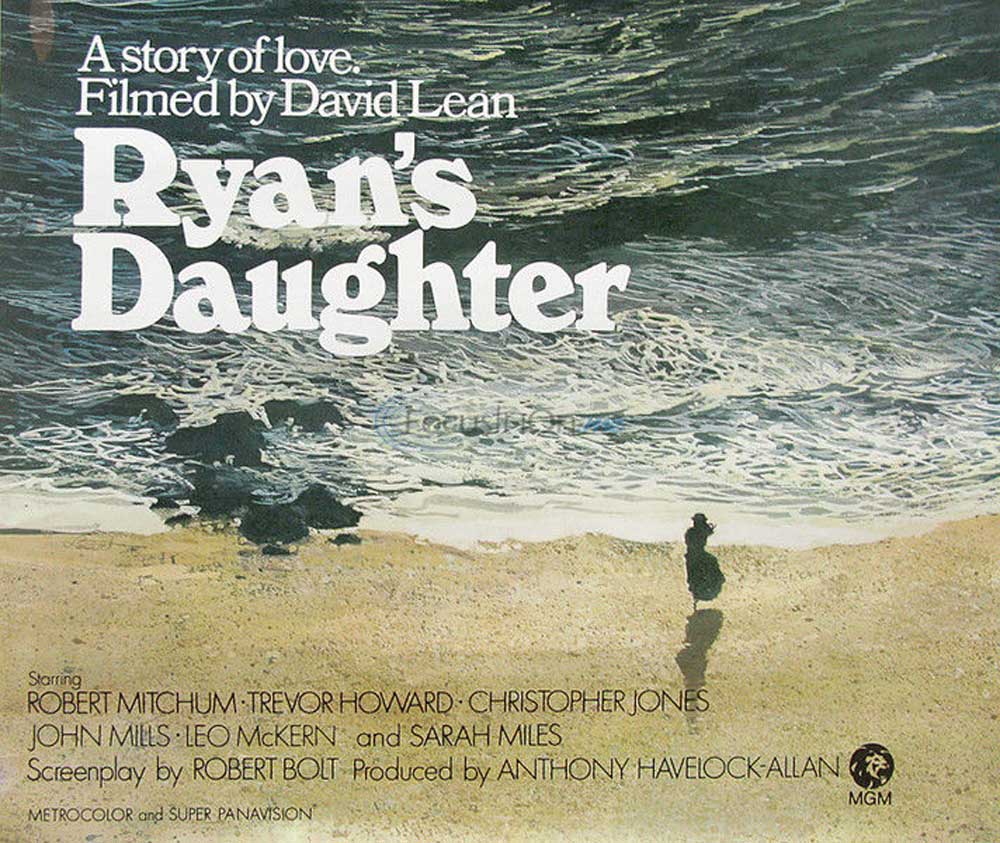

- MGM/COURTESY

I want to like “Ryan’s Daughter” more than I actually do.

Every director, no matter how prolific or talented, will always, eventually, make a movie that either rubs you the wrong way or simply doesn’t connect.

Even my beloved Michael Mann has done this, as has Steven Spielberg. I’m sure even Edgar Wright and Darren Aronofsky will do so as well. David Lean, as taken as I’ve been with nearly every other film of his I’ve seen, seems to stumble with his 1970 film.

Set in a fictional Irish village, “Ryan’s Daughter” mixes a love story with World War I politics, all set against some stunning imagery.

Lean’s visual prowess is certainly not among the issues I have with the film, thankfully. No one packs a frame with natural beauty quite like Lean does, and that’s particularly true here. He takes tremendous advantage of the gorgeous island setting and crafts each frame with a painterly touch. The clouds, the lush vegetation, the crashing waves, it’s all captured with stunning fidelity.

If only the story was as captivating as the imagery.

Sarah Miles is Rosy Ryan — a timid young girl who falls in love with Charles Shaughnessy (Robert Mitchum), the island’s school teacher. They quickly get married, but just as quickly find there’s little between them, trapping the two in a loveless marriage.

Given her disillusion with marriage, Rosy soon finds her gaze falling on Maj. Doryan (Christopher Jones), a British officer stationed on the island. They quickly fall into an extramarital affair, with Rosy disappearing out of town for hours on end. This complicates things not only in her marriage, but also in the fact that the island’s residents are staunchly nationalist and exclusionary.

As you can probably guess, things go horribly wrong, especially once gun smugglers are exposed and Rosy’s affair is revealed.

I just never connected with any part of this. Rosy, from the beginning, is shown to be naïve and shortsighted with little else to define her character, so it’s difficult to drum up sympathy/empathy for her once she starts making bad decisions. I almost came to be in Charles’ corner, but he seemed to be trapped in a situation of his own making. He’s dead-eyed on his wedding day, but no one forced him to marry this girl.

Doryan is a somewhat interesting figure, but he’s mostly mute (due to largely to Jones being a terrible actor, which Lean didn’t discover until it was too late) so there’s not a whole lot for him to do save for sleeping with Rosy and having PTSD flashbacks (which are, admittedly, very well realized).

The only two truly compelling characters are Father Collins (Trevor Howard), the resident Catholic priest, and Michael (John Mills, reuniting with Lean after working together decades before in “Great Expectations”), the village idiot whom everyone, save for Father Collins, ruthlessly chastises.

It’s hard to know what to think of something that clearly is built around eliciting a strong connection to the viewer in order to be effective. I feel like I should have had something more here, I just can’t seem to muster it. I’d say maybe I need to revisit it eventually, but I’m hardly compelled enough to do so.

Oh well. It doesn’t change the fact Lean was a marvelous filmmaker, and that even in his failures he still managed to produce truly cinematic works. I’m looking forward to going back to his works and picking through the other few I have yet to watch.

Next week, I begin my series on Frank Capra, with a review of “Lady for a Day.”

Every week, Entertainment Editor Stewart Smith brings a new entry in “Catching Up On…” an ongoing series attempting to fill in the gaps of his cinematic education.