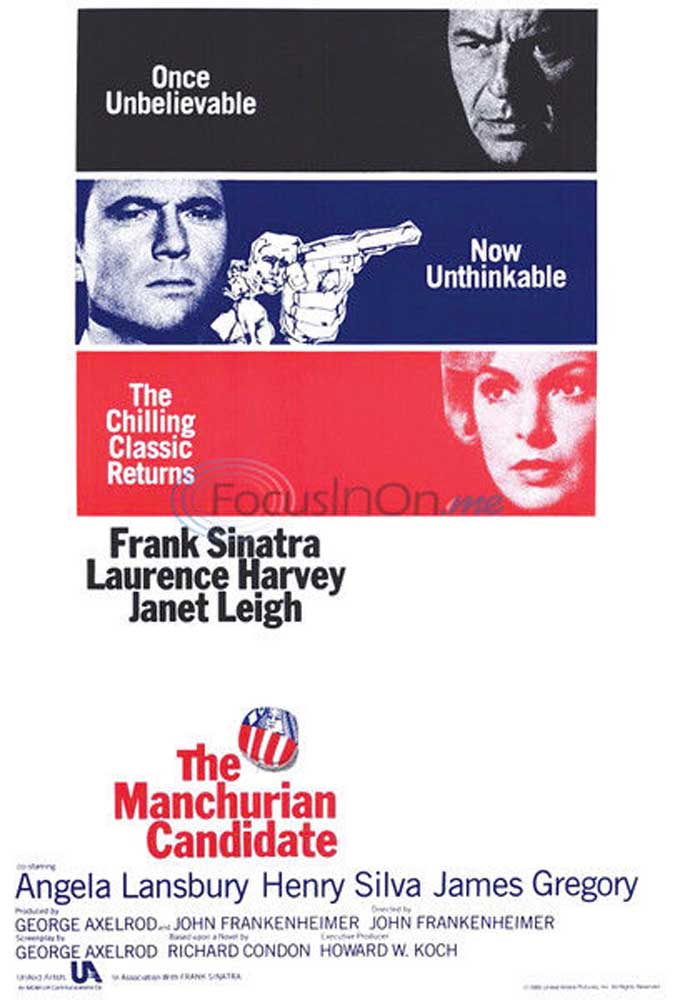

Catching up on John Frankenheimer: ‘The Manchurian Candidate’

Published 10:07 pm Tuesday, August 27, 2013

- Courtesy

I must admit, my desire to do a series on John Frankenheimer stems from my love of a single film: “Ronin.”

“Ronin” stands as one of the all-time great modern action films, one that will forever be held up as a pristine example of tight scripting and characterization, as well as some of the best car chases ever committed to celluloid.

But what of Frankenheimer’s other works? The man directed nearly 30 feature films and dozens of television episodes and made- for-TV movies. What’s to be found in his films as he worked with actors such as Kirk Douglas, Burt Lancaster, Frank Sinatra and James Caan? Well, if “The Manchurian Candidate” is any indication, his proficiency for making smart, tightly wound films was there from the beginning of his feature career.

“The Manchurian Candidate” is kind of perfect for the time it arrived. Initially released in 1962, it fed directly off the Cold War paranoia that ran rampant at the time. Laurence Harvey plays Raymond Shaw, a Korean War staff sergeant who is given a congressional medal of honor for his bravery in rescuing his platoon from enemy fire.

In reality, however, he and his platoon were captured by a Communist cabal, brainwashed and then released back into the wild. Raymond, though, was specifically conditioned and trained to be a sleeper agent, able to be activated by a single phone call. The only one who suspects something is truly amiss is Capt. Bennett Marco (Frank Sinatra).

The idea of Communists brainwashing, hypnotizing and then remotely voice-activating a sleeper agent is kind of silly now, but it’s remarkable how effective the film still is in spite of this (Admittedly, Showtime’s “Homeland” has shown that the concept can still feel quite real and relevant when done today). Frankenheimer plays things so straight and serious that you kind of can’t help but buy into it. This seemed like a real possibility to everyone involved, and that comes across in what we get on-screen.

What truly stands out, though, is Frankenheimer’s sense of style. His use of Dutch angles, blurred focus and a creeping sense that someone is always watching Raymond; there’s a visual verve to this film that stands out among its contemporaries.

It’s also worth mentioning the surprisingly well-choreographed martial arts fight between Sinatra and Henry Silva (whose performance induced cringes as he attempts to portray a Korean man) in Raymond’s apartment. With a little more flash, it feels like it could be used in almost any contemporary action scene, which is saying something as most fights of the sort from that era don’t age well at all.

This may lack a lot of the punch it had at the time of its release, but that can’t really be helped — the Red Scare has long since dissolved and our political paranoia is found elsewhere. But it’s a testament to Frankenheimer’s skill behind the lens that the film still moves so well despite this.

Next week, I’ll continue my series on Frankenheimer with a review of “Seven Days in May,” followed by “The Train,” “Grand Prix” and “Ronin.”

Every week, Entertainment Editor Stewart Smith brings a new entry in “Catching Up On …” an ongoing series attempting to fill in the gaps of his cinematic education.