Book World: Tennis star, fashion designer, activist . . . spy?

Published 10:38 pm Wednesday, August 12, 2020

- Book World: Tennis star, fashion designer, activist . . . spy?

Before Serena Williams, before Billie Jean King, before Althea Gibson, there was Alice Marble, a glamorous powerhouse in shorts who rose from the public courts of San Francisco to dominate women’s tennis in the late 1930s and change the game.

Although Marble was a household name, with her face on a line of Wilson tennis rackets, her legend has since faded like the wooden frames of yesteryear. Sports in pandemic-ravaged 2020 have leaned heavily on nostalgia, so the timing seems right for a book about a multitalented pioneer with an enigmatic past.

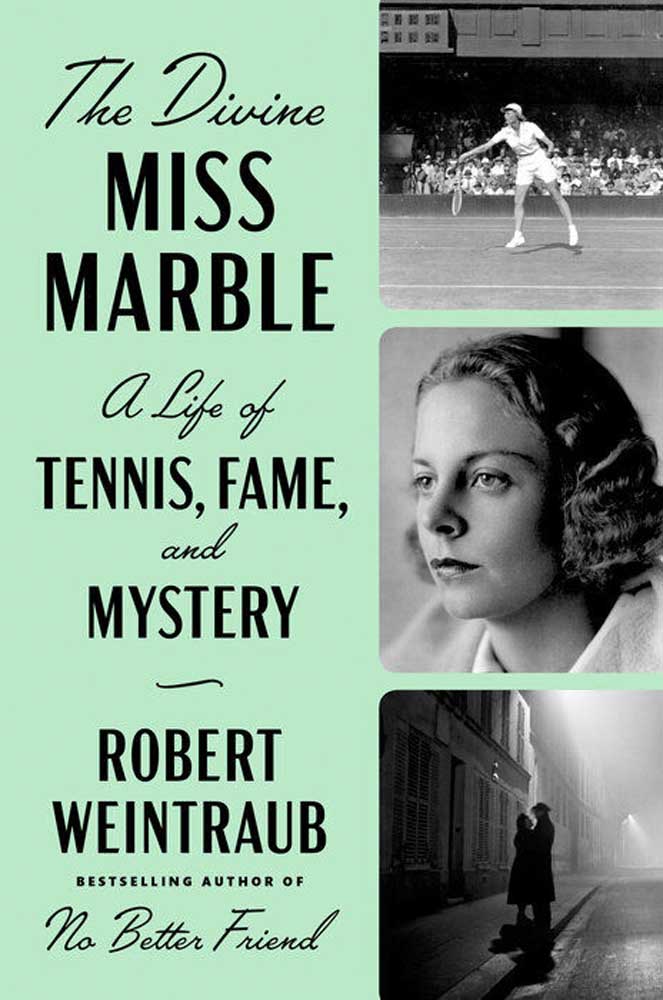

In Robert Weintraub’s exhaustive biography, “The Divine Miss Marble: A Life of Tennis, Fame, and Mystery,” he transports the reader into Marble’s vibrant world: her baseball beginnings, her recovery from tuberculosis, her triumphs at Forest Hills and Wimbledon, and her San Simeon parties with the Hollywood elite. She designed her own clothing line, sang cabaret, wrote inserts on real female heroes at Marvel Comics for “Wonder Woman,” and penned a column advocating for Gibson that blasted tennis officials for not integrating the sport.

Marble had a close, and perhaps sexual, relationship with her Svengali coach, Eleanor Tennant. She may have briefly been married to an Army captain. But then there’s the most sensational mystery surrounding Marble, tantalizingly promised in the subtitle and the preface when “a shot rang out” following a car chase in Switzerland.

Was Marble a World War II spy for her country?

“Alice Marble may be mysterious, but she doesn’t disappoint,” Weintraub offers.

But ultimately, the biography as billed does disappoint. Despite his best investigative efforts, which Weintraub laboriously details in nearly 400 pages of text, he could not solve that central mystery of Marble, who died in 1990 at age 77. Rather than feel frustration, he writes, he appreciated “the good fortune I had to immerse myself in her life away from the court, to more fully understand the world of this great champion, woman, human being.”

A lack of resolution isn’t the only perplexing issue for this biography. Weintraub’s writing is anachronistic, a battle between clever and cloying that, upon instant replay, lands just outside the line.

Every chapter is named for a movie — presumably because of Marble’s association, through her coach, with Hollywood; the book dishes delightful stories of her friendship with Carole Lombard and her leading man, Clark Gable.

The gimmick feels strained, even for those who can appreciate the comedy of both “Pitch Perfect” and “Defending Your Life.” For the meaty chapter on Marble’s fight for Gibson’s inclusion, Weintraub goes, predictably, with “Do the Right Thing.” Spike Lee’s 1989 epic on race relations and police brutality in Brooklyn has taken on greater relevance during the George Floyd protests of 2020.

Marble’s words say it best. “If tennis is a sport for ladies and gentlemen,” she wrote in American Lawn Tennis, “it’s also time we acted a little more like gentlepeople and less like sanctimonious hypocrites.”

Weintraub relies on primary accounts from Marble’s two autobiographies, which he reminds readers are contradictory, if not inflated: “Courting Danger” (1991) and “The Road to Wimbledon” (1946). He infuses the match narrative with news accounts of her 18 major titles, including four singles championships at the U.S. Nationals, the precursor to the U.S. Open.

If only Weintraub, the best-selling author of “No Better Friend,” about a World War II British prisoner and his dog, used his plentiful narrator’s asides to include more women. Surprisingly for a book about women’s tennis, he leaves out obvious comparisons to Serena Williams and Venus Williams. Marble designed and promoted her own clothing line, just like Venus Williams. Marble was called “masculine” because of her booming serve and aggressive groundstrokes, just like Serena Williams, who owns 39 Grand Slam titles.

When Marble insisted on wearing shorts instead of inhibiting long skirts, she made a bold fashion statement that women still make. “It is hard to imagine the shock that caused at first from today’s perspective, where the idea of wearing anything but shorts for competitive tennis is asinine,” Weintraub writes. Women, of course, now wear dresses, skirts, shorts and, like Serena first did in 2002, catsuits.

The author is more successful when he removes himself and re-creates Marble’s first victory at Forest Hills in 1936, when she defied doubting doctors and the tyrannical head of the U.S. Lawn Tennis Association. “My Favorite Year,” the chapter about 1939, builds suspense for Marble’s victory at Wimbledon before the war intervened. She swept all three titles on one afternoon, including women’s doubles and mixed doubles with her partner, Bobby Riggs.

Tennant coached them both, and Weintraub shows Marble’s disdain for Riggs, the “bad boy of tennis.” In her own coaching career, Marble briefly guided a teenage Billie Jean King. Too bad the book only has a comment from Tennant about the 1973 landmark “Battle of the Sexes” match when King crushed Riggs.

Though mercurial, Marble was clearly a true Renaissance woman, a survivor of car crashes and illnesses, who possessed “The Will to Win.” That was the title of the talk — crafted with help from Eleanor Roosevelt’s speechwriter — that Marble gave throughout her life. It’s a dreamy, indomitable life worth reading about as today’s tennis tries to return to form.

– — –

Robbins is a freelance writer in New York. She covered tennis for the New York Times from 2000 to 2010.

Author Information:

Liz Robbins is a freelance writer in New York. She covered tennis for the New York Times from 2000 to 2010.