East Texas rancher upholds ranching legacy, breaks through racial barriers

Published 5:45 am Saturday, February 17, 2024

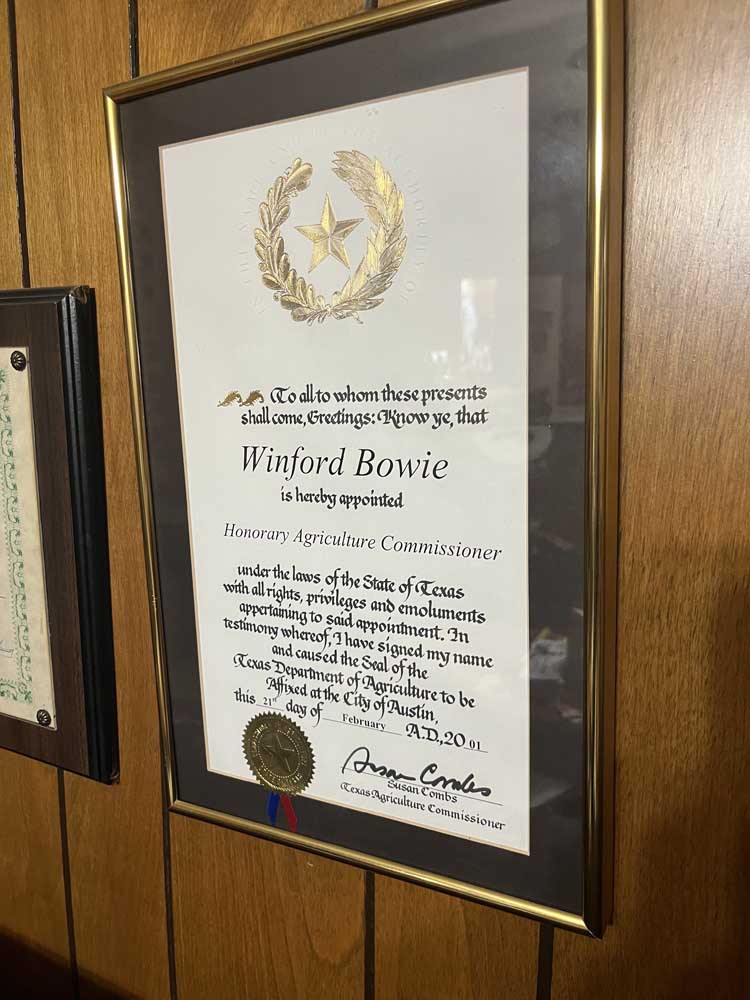

- A certificate from the State of Texas naming Winford Bowie as Honorary Agriculture Commissioner.

Editor’s Note: This is one of a series of feature stories published in honor of Black History Month.

An East Texas rancher is upholding his family’s legacy and has broken through racial barriers to get to where he is today.

Trending

Winford Bowie, who will turn 88 next month, said he remembers the days when he and his ancestors couldn’t do anything but work. Bowie’s grandfather came to East Texas from Alabama in 1892 to purchase land with the objective of being a farmer. Bowie, 87, upholds the family legacy today as he runs the 132-year-old ranch.

“For a Black man, there was nothing for us to do but farm work,” Bowie said. “But my granddaddy was what we would call a farmhand rancher because at that time there wasn’t any work to do other than farm work.”

Bowie’s grandfather bought 162 acres of land, becoming among the first of many Black ranchers in Texas.

“He got it for real cheap,” Bowie said. “But it was a big deal for a Black man to buy land then.”

The Bowie family worked hard to provide not only for themselves but for the community by selling the meat from cattle, as well as milk and butter. Just two generations out of slavery, by 1910 Black farmers had amassed more than 16 million acres of land and made up about 14 percent of farmers, according to the Associated Press. The fruit of their labors fed much of America.

“My mother had a big garden and we raised everything we had,” Bowie said. “We had a good living, eating healthy and getting what we needed.”

Trending

Born in Smith County, Bowie was the sixth child of nine. Although he was an unenthusiastic student in his youth, he saw success as an athlete in basketball and track at Stanton High School. He also attended an agricultural program in school, budding his interest in ranching.

“When we got up to a certain age, my dad gave … each one of us a calf,” Bowie said. “When it got to be my time, he was gonna give me one.”

But at the age of 15, Bowie decided to approach his father with the proposition of buying his first calf.

“This will always let me know that I have something of my own and that would motivate me to take care of it,” Bowie said. “So, I got two calves — they were heifers — and started to take care of them.”

Although he completed high school —and was even offered athletic scholarships — he declined to go to college after graduation and went right to work in 1957 at the Tyler Packing Company, where he worked as a janitor, delivery worker, butcher and beef grader.

Although he was a hard worker, his presence was often met with racial challenges and discrimination. Bowie endured racial slurs.

“I heard it a lot,” Bowie said. “Regardless of how hard a Black man worked, that word was always around to be heard.”

Bowie decided to advance his education by completing various courses and certification programs in Business Management at Tyler Junior College, Baylor and LeTourneau University.

After putting some time in at the packing plant as the first Black butcher and first Black supervisor, Bowie was hired by the Kelly Springfield Tire Company, which would later be known as the Goodyear Tire & Rubber Company.

“I was the eight out of 524 employees,” Bowie said. “There weren’t but eight Blacks out there, and most of them had college education; some of them had college degrees and others had some college experience.”

He started out as a janitor and was later promoted to the position of tire builder, and broke racial barriers again by becoming the first Black supervisor at the Springfield Tire Company.

“Building tires… now that’s a technique job,” he said. “That’s a skill work… and I did that for about five years.”

One evening as Bowie was heading home for the day, his supervisor asked him to stop by the office.

“I thought I had done something wrong,” Bowie said. “I thought I had messed up and they wanted it corrected.”

However, much to his surprise, they called him in to offer him a supervisor role.

“I said, ‘but you don’t have (a) Black supervisor,’” Bowie said. “He said that they needed one because… the Civil Rights bill passed and there is a quota they’re supposed to meet for a plant like that.”

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 included a provision prohibiting discrimination in employment. Employers who contract with the government or receive federal funds are required to document their affirmative action practices and metrics. Affirmative action is a set of procedures designed to eliminate unlawful discrimination among applicants, remedy the results of such prior discrimination, and prevent such discrimination in the future, according to Cornell Law.

While the goal was to offer more opportunities for minorities, many employers were using the color of an applicant’s skin to fill in numbers, regardless of their qualifications.

By 1969, some lawmakers argued anti-discrimination laws weren’t enough to end inequality. The Equal Employment Opportunity Act came about and while specific quotas remained illegal, the government pushed employers to develop affirmative action programs to seek out, hire and promote qualified minority workers.

“They had some Blacks be considered before I got there, to try to be a supervisor … to try them out, but they never did make the grade,” Bowie said. “So, I was kind of doubting … because something had to be wrong. But (my supervisor) said, ‘You’re the tire builder, you’re one of the good ones. That’s why we pick you.’”

With a new dress code to follow, Bowie started the next morning as a tire building supervisor. The position allowed him the opportunity to recruit and promote other qualified people of color who may have been overlooked.

Bowie served as manager for over 20 years before retiring at the age of 55 so he could enjoy ranching.

“The cattle was the one that helped me to get to where I am right now, to help me to buy more land,” he said. “Because after I got out there, I was able to buy more. I was making money and I was investing my money in land.”

In a 2022 report released earlier this week, the USDA’s Census of Agriculture estimated that of the 3.4 million agricultural producers in the United States, roughly 41,800 are Black, and nearly a quarter of them are located in Texas.

In Smith County, there are at least 346 Black farmers and ranchers.

Before he got out of high school, Bowie had already begun the process of purchasing land from his family, specifically from his aunts and uncles as they had no interest in running the ranch.

“I’d buy that one acre at a time,” he said. “I was just doing a little farm work in between because at that time, land was cheap.”

In 2001, Bowie received the honor of being one of 10 successful Black ranchers in East Texas. He was also named Honorary Agriculture Commissions for the day by former Agriculture Commissioner Susan Combs. He’s also been recognized locally by the Texas African American Museum in Tyler.

In addition to those honors, the land Bowie lives and ranches on has been recognized as Family Heritage Land by the Texas Department of Agriculture since it is land that was purchased by his ancestors more than a century ago, continuing the use of its ranching purpose today.

Settling into his retirement, Bowie has hired folks to help him with the ranch.

“I played a lot of sports and wore my knees down,” Bowie said. “Time… it will catch up with you.”

Despite the racial challenges he’s faced over the years, Bowie has always been a strong believer in treating people kindly — no matter what.

“I came up on both sides of the road,” he said. “I know the good and the bad and part of the ugly, but there’s some good people in all races and there’s some bad ones in all races.”

For more than six decades, Bowie has served as a deacon at New Hope Baptist Church in Bullard, a position he earned at a young age.

“You can’t make nobody like you but… you can still treat people the way you want to be treated,” he said. “I thank God I’ve been around here long enough to know that to see it for myself.”

Bowie is turning 88 next month, and while he may have slowed down a little bit on the ranch, his future remains dedicated to carrying on his family’s strong legacy of ranching in East Texas.