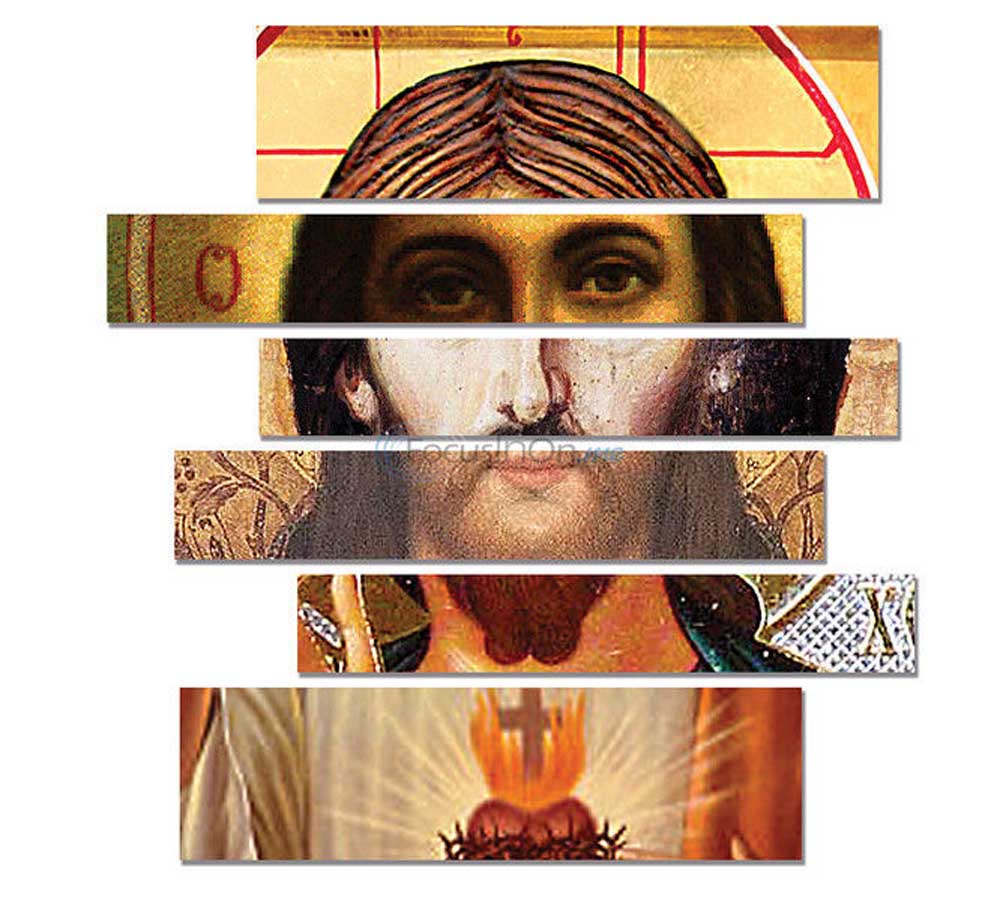

The many faces of Jesus: Christian savior’s depiction in art has changed throughout the ages

Published 11:20 pm Friday, May 9, 2014

- Article by Rebecca Hoeffner rhoeffner@tylerpaper.com Page design by Derek Kuhn/Staff Graphic

For thousands of years, artists have been painting interpretations of Christ. And the religious leader has gone through some transformations over the centuries.

“There is no physical description of Jesus in the Scriptures,” said David Dykes, senior pastor of Green Acres Baptist Church, who did post-doctoral work at Cambridge University in England in the field of religious art with an emphasis on the Renaissance period. His thesis was that art had a greater influence on the developing beliefs of the Church than did theology.

“How Christ looked was probably passed down through oral description from the two or three generations who knew him,” he said.

Christ wasn’t portrayed in art until Christians began to feel safe from persecution, Dykes said. The earliest known piece of art depicting Jesus was found painted on the wall of a Syrian church, dated around 235 AD, Dykes said. The piece depicts a famous story of Christ healing a lame man. Interestingly, Christ is depicted in this, and even a few later pieces, as youthful and without the characteristic beard he develops in later portrayals.

“The earliest images of Jesus depicted him as the ‘Good Shepherd,'” said Dr. Elizabeth Lisot, an art history professor at the University of Texas at Tyler, in an email exchange. “This portrayal emphasized his character as a pastoral leader, helping to bring the lost sheep into the fold. As the early Church was spread the “Good News” – the Gospel – Jesus was understood as a caregiver who would accept Pagan, Jew or gentile. He was depicted without a beard, holding a lamb. This was not an image unknown to an agrarian people; it had precedents in Pagan art and religion, and therefore would be understood by the viewer to represent a caring divinity.”

Dr. Lisot also said that Christ wasn’t depicted on the cross until after the punishment was outlawed in Rome.

“The earliest known, surviving, depiction of Jesus on the cross comes from a small ivory carved box. The crucifixion is shown, and at the same time, the suicide of Judas. Christ is beardless and stands in a ‘triumphant’ position with arms extended showing the nails in his hands. The Virgin Mary and the Apostle John stand at one side, and the centurion, Longinus, stabs Him with the lance on the other (the lance is missing). To the left Judas hangs himself from a tree with his bag of silver coins at his feet.”

Slowly, the way Christ was depicted —and the messages from those images began to change.

“As Christianity developed, defining its doctrines in contrast to Paganism, heresies and various mystery cults, it began to emphasis Jesus’ role as a law giver,” Dr. Lisot said. “Pagans did not have moral laws given to them by their gods. Zeus could hardly dictate a commandment against adultery. This emphasis on Christian moral law was reflected in depictions of Christ, who is shown as a stern ruler, a ‘pantokrator,’ who is almighty and all-powerful. People in the Roman and Byzantine world experienced ultimate authority in the form of the emperor; therefore, they could understand an idea of god as an omnipotent judge who called them to follow the doctrines of the Church. Jesus was understood to be a co-ruler with God the Father and these images emphasized that He was God. Though Christ was shown with or without a beard in the Early Church, more commonly after the sixth century, he was depicted with a beard in the East and the West.”

As history crept into the Middle Ages, art depicting Christ became more and more prevalent, Dr. Lisot said.

“Images of Christ carved in stone or painted in fresco were created all over Europe,” she said in the email. “Though Jesus was still shown as a judge, who separated the blessed from the damned at the Last Judgment, there was also an emphasis on his dual natures. Jesus was both fully human and fully divine.”

The art was also affected by what people were going through at the time.

“Images of Christ on the Cross became particularly pitiful after the Black Plague of 1348, as so many people had died (close to 60 percent of the population in Europe),” she said. “The survivors had suffered a great deal. They could relate to a suffering god.”

The Renaissance ushered in an age of realistic paintings, and Christ was no exception. Dykes, who focused on the Renaissance period during his studies, said “Christ at the Column,” by Antonello da Messina is his favorite.

“He’s a manly looking Jesus,” he said. “The reality was that Jesus was the son of a carpenter with dirt under His fingernails and hair on His chest.”

Depictions of Christ still continue today, and remain widely up to interpretation.