Journals from behind the wire

Published 9:03 pm Tuesday, December 2, 2014

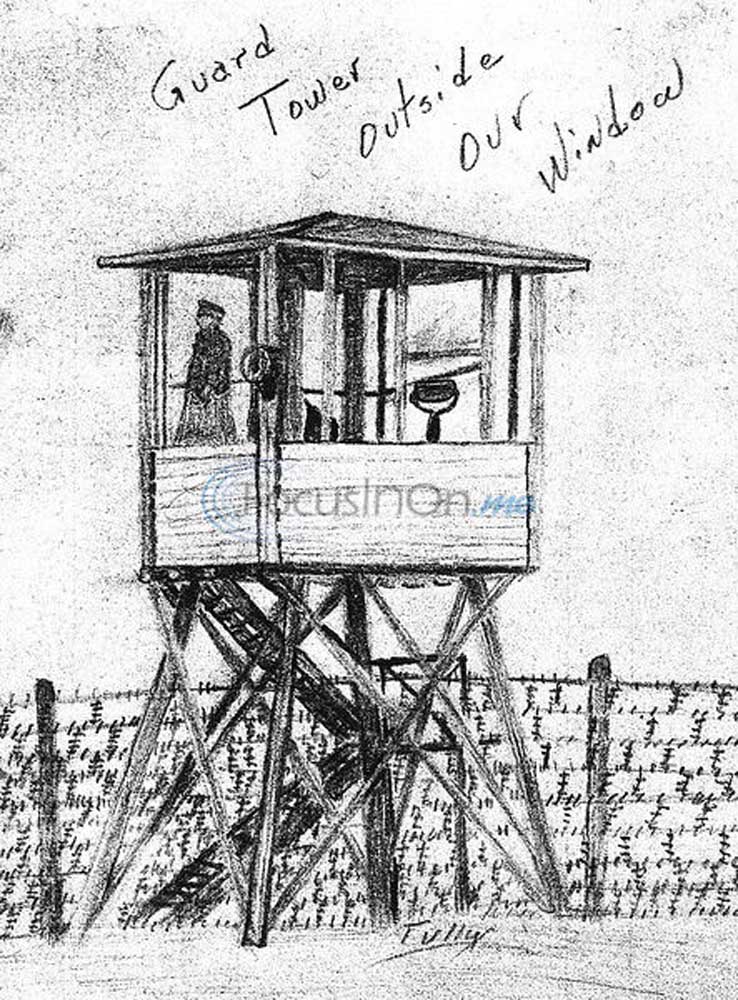

- O.D. Tully's drawing of a guard tower at the POW camp in which he spent 18 months during World War II. Tully was an officer aboard the B-17 Mission Belle, which was shot down Dec. 1, 1943.

“The Wire,” he is always there, blocking every dream, every plan, every vain soaring of your enthusiasm. “The Wire” is at the end of every road; he is gaunt and he is cold, at dusk he frames the western sun in a black spider web of prickly steel. Even the sun is captive.”

From “The POW Journals of Claudio ‘Steve’ CaranoKrems, Austria 1944”

Steve Carano didn’t know the men he was assigned to fly with that cold December day 71 years ago.

His own pilot was grounded, and he reported to the ready room expecting to sit out this day’s raid on Cologne, Germany.

Instead, searching the roster, he found himself assigned as substitute radio operator to “097,” the B-17 known to its crew as the Mission Belle. His new flight officer was Harlan Sunde, a man he quickly decided was “one of the finest men I had met in the Army.” Together, they headed for their assigned bomber, where he met Carlton Josephson, a waist gunner he described as the practical joker of the crew.

Aboard the Mission Belle, preparing for a 7:30 a.m. takeoff, Carano found the rest of the 10-man crew … Lt. O.D. Tully, the first aid officer; Roger Christensen, navigator; John F. Healy, the tail gunner; Charles J. Culver, an easygoing Kentuckian; Doyle McCutchen, an Idaho farm boy whose small stature made him an ideal ball turret gunner; William P. “Hap” England and James W. Sweaney, another replacement in the co-pilot’s seat.

That mission, on Dec. 1, 1943, would be the Mission Belle’s seventh over Germany, bombing the ball bearing factory at Leverkusen in the heavily defended Ruhr Valley. Statistically, bomber crew members could expect to complete only five and a half missions before being killed, missing in action, wounded or becoming a prisoner of war. The crew was living on borrowed time.

Josephson was fairly new to the crew, and his previous missions had all been scrubbed short of the target. He had yet to see an enemy fighter. When the landing gear failed to retract, this one looked equally doubtful, but he put his back to the manual crank and had them up before the plane was over the English Channel.

The attack itself went bad quickly for the Mission Belle. Flak over Leverkusen was heavy and accurate, and the Flying Fortress was severely damaged during the bomb run. With one engine ablaze, the plane dropped out of formation and lost altitude.

Alone and vulnerable in the skies over Germany, the crew watched the surviving bombers disappear to the west — heading for the safety of England. An easy target for German fighters, they were blasted from all sides. Half their 13 guns were knocked out, and soon all but one of the 10 men aboard were severely wounded. Healy, in the shredded tail, was dead.

Carano’s journal describes a desperate fight for survival as the stricken plane dove into the clouds for cover, banking wildly to avoid enemy fighters closing in for the kill. Too low to bail out, they watched soldiers on the ground firing up at them with small arms.

The wounded plane could no longer stay aloft, and co-pilot Sweaney ditched the B-17 in the swift waters of the Rhine River. A German pilot made one last pass, tipping his wings in salute as the plane sank. Sunde, the mortally wounded pilot, made it out but drowned in the icy water. McCutchen, the ball turret gunner, and Healy, the tail gunner, went down with the plane.

The other seven made it to shore, where villagers bandaged their wounds and warmed them with hot coffee. Carlton Josephson wrote about the crash in his memoirs. His son, Paul Josephson, who lives in Tyler, said his father “didn’t talk much about his experiences in the war until a few years before he died in 2001,” but left some of those memories behind in a brief “War Journal.”

Josephson described the carnage in the blasted core of the plane, torn by flak and stitched by dozens of 30-caliber bullets. He recalled the blood, the shredded metal and the wounded men helping each other — all those in the rear of the plane suffered multiple wounds. Josephson had been shot four times.

Of the B-17’s plunge into the Rhine, he wrote: “It seemed like hours in the water before I came to the surface for a breath but in reality it was only a few seconds. In those few seconds I lived a lifetime and thought of my wife, folks and home … and told myself I just had to get out. Coming out of the water, my helmet had been knocked over my eyes, my chute was wet and heavy but there was Steve on top of the radio hatch ready to pull me out …”

He and Steve Carano had known each other less than a day. Now a wounded Carano pulled the badly injured Josephson into the safety of the life raft. German soldiers would soon transport them to Austria, where they would become “like brothers” during the next year and a half as prisoners of war in Stalag 17B.

Josephson in his short “War Journal” described prison camp life as “rough,” saying winter in Krems, Austria was “very cold and miserable as we had inadequate blankets and no heat. Our meals consisted of coffee from our Red Cross parcels, while the other two meals were soup. What a concoction! Everything from fleas to horses was used in this soup. The bread was like armor plate and often had wood chips in it.”

Josephson kept his journal short for fear German censors would take it from him, but wrote that his memories could fill a book. (Excerpts from his “War Journal” are reprinted in more detail as a “My Story” segment on this page.)

Carano, on the other hand, did fill a book. One paragraph from his book, “Not Without Honor: the Nazi POW Journal of Steve Carano,” describes his emotions near the end of his captivity.

“Some of us have been prisoners of war for eighteen months. Eighteen months is a year and a half, is seventy-two weeks, is five hundred and four days, is 12,096 hours, is 725,760 minutes. How long is a minute? A minute is a very long time. You can review your lifetime in a minute.”

Josephson and Carano were just two of almost 94,000 American POWs held by the German Army. A third of the POWs in the European theater were from aircrews of about 12,000 heavy bombers shot down over Germany.

###

POWs held by the Japanese found even harsher treatment. Of more than 27,000 Americans captured by Japan, 11,107, or 40 percent, died in captivity. National POW/MIA Recognition Day is observed on the third Friday of September every year. Dave Berry is editor of the Tyler Morning Telegraph. His column runs each Wednesday on the front of the My Generation section.