Doctor remembers last moments of Kennedy’s life

Published 10:51 pm Friday, November 21, 2014

Just after lunchtime 51 years ago, Dr. Robert McClelland was in a conference room, showing a group of students a film on surgical techniques on the second floor of Parkland Hospital in Dallas when a coworker brought the news that President John F. Kennedy was coming in with a gunshot wound.

As he headed downstairs with his friend and colleague Dr. Charles Crenshaw, McClelland hoped the news was misleading.

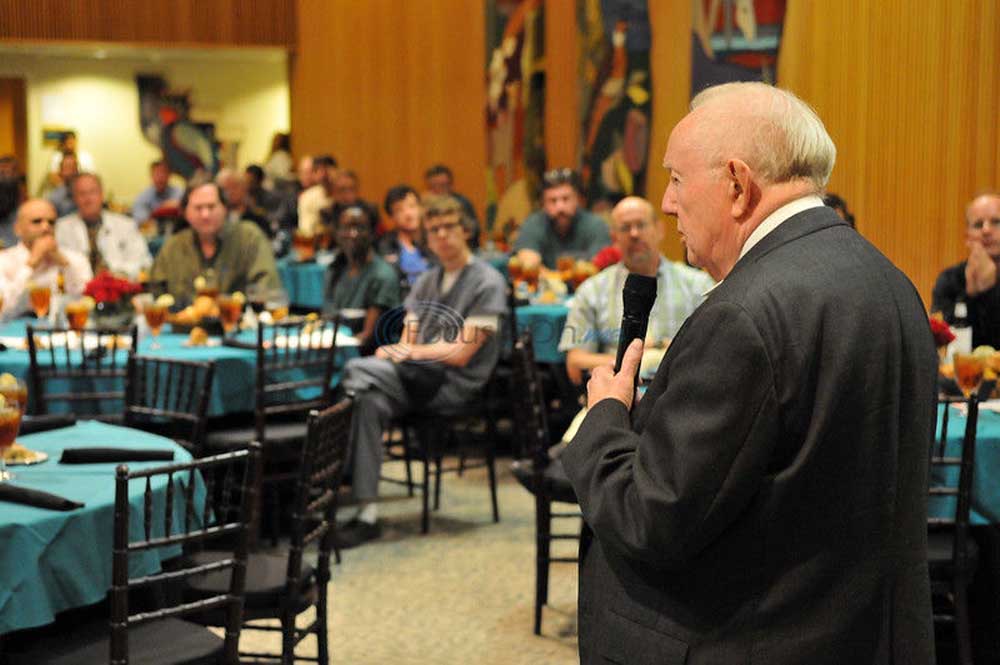

“We often get calls about some terrible thing that turns out it’s not so terrible after all. … Hopefully it’s not as bad as they said it was,” the doctor told a group of ETMC physicians last month at a private speaking event.

McClelland is one of the few still-living doctors who experienced the well-publicized and speculated events surrounding the president’s assassination. He was in the trauma room with the president and, later, with alleged killer Lee Harvey Oswald, who was shot while in police custody two days later.

McClelland elbowed through crowded hallways to get to the lineup of trauma rooms on the first floor on the hospital.

“I saw Mrs. Kennedy sitting on a folding chair outside Trauma 1, and I knew immediately it was just as bad as they said it was going to be,” he said. “I had to force myself to walk toward her. I might be the only surgeon there at Parkland.”

As the doors to the room opened, he was relieved to see others already had started to work on the president.

“It was a horrific sight of the president lying on his back in the trauma room on a gurney with a bright light shining on his bloody head,” McClelland said. “I was at the same time gratified to see I was not by myself.”

The doctors were looking at a bullet hole in the president’s neck.

Dr. McClelland was tasked with performing a tracheotomy to help the president breathe when he glanced down at the side of his head.

“I said, ‘My God, have you seen the back of his head?'” the physician recalled. “The right side of the back of his head (was) gone. The whole back half of the right half of the cranial fossa was empty. It was clear that this was a fatal wound.”

Doctors kept busily trying to keep the president alive. McClelland said the president maintained excellent cardiac activity for about five minutes and then all of a sudden the cardiac monitor flat-lined. Kennedy was pronounced dead a 1 p.m. Nov. 22, 1963.

By that time the room was packed with people watching the activity, and in the bustle for crowd to leave, McClelland and Dr. Charles Baxter were caught behind a gurney and pushed against the wall. As they went to leave, the Rev. Oscar Huber came in to read the president his last rites.

“Dr. Baxter froze against the wall, and we found ourselves the unwelcome witness to the president’s last rites,” McClelland said. “I couldn’t hear but the first thing he said, “Thou livest,” and I couldn’t hear anything else. He spoke in such a quiet voice.”

After the rites were read, Mrs. Jacqueline Kennedy came into the room and quietly asked the priest if the last rites were granted.

“She was completely composed,” McClelland said. “She was not crying. She stood there completely calm, didn’t saying anything more. Then she exchanged a ring from her finger to the president’s finger and a ring from his finger to her finger.”

Slowly the First Lady walked to the end of the gurney, kissed the president’s foot and walked out of the room.

The president died on a Friday afternoon. The next day was quiet except for an extensive amount of news coverage, and on Sunday morning McClelland and his wife went to church.

The couple was getting ready to go to lunch when McClelland saw the news coverage of Lee Harvey Oswald’s shooting. He was fatally shot by while in police custody as they tried to transfer him from one facility to another.

“I could hear the voice saying, ‘He’s been shot. He’s been shot. He’s been shot,” the physician recalled. “I thought, ‘my goodness, what now,” (before) I saw the picture of Oswald (who had) just been shot by (Jack) Ruby.”

McClelland skipped lunch and headed to the hospital. He said the hospital was a beehive of activity surrounding Trauma Room 2, across the hall from where the president had been treated two days earlier.

By the time McClelland was scrubbed in, Oswald already was on the operating table.

McClelland said had Ruby’s bullets gone where they intended,

“The bullets that killed him might not have killed him, had Oswald not seen him coming at him with a pistol and naturally turned,” McClelland said.

Facing straight on, the bullets likely would have missed major organs and vessels, but as Oswald turned to his left, the bullets were given access to more tissues as they cut across his body instead of through it.

McClelland said he was surprised Oswald didn’t bleed out before he made it to the hospital.

Doctors opened up his chest and manually massaged his heart to try to keep it pumping, before it was obvious he wasn’t going to recover.

The police officer handcuffed to Oswald when he was shot was waiting at a nurse’s station for news on Oswald’s condition.

After doctors told him, the police officer shared a little of what happened.

The officer told doctors as Oswald sank to the floor at the police station, he gave his prisoner a chance to speak.

“(The police officer) said, ‘Son you’re hurt real bad. Would you like to tell me anything now?” McClelland recalled. “Oswald looked at him for a long several seconds and shook his head real widely from side to side as if he didn’t want to say anything.”

Looking into Oswald’s eyes, the officer said he believes a secret died with Oswald that day. McClelland agreed.

“I will believe until the day I die that he did want to say something but thought better of it and closed his eyes, and that is the last thing he did,” McClelland said.