East Texas veteran’s suicide sparks criticism over VA healthcare

Published 7:28 am Tuesday, July 16, 2024

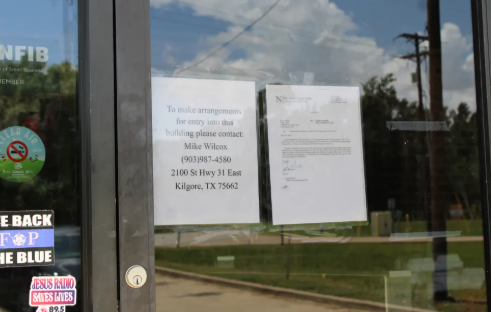

- Chris Burroughs is becoming an advocate to raise awareness about veterans' mental health and suicide prevention—an effort that could have made a difference in Dan's story. (Katecey Harrell/ Tyler Morning Telegraph)

In the four months before his death, Bullard veteran Daniel “Dan” Burroughs sought treatment for physical ailments. At the same time, he struggled with declining mental health.

“The difference in him in the way he talked these last few months, the way he walked, the way he looked – he never looked like that,” his son Chris Burroughs said. “I’d have to beg him to go outside, to reward himself. … It was a struggle to get him to eat, to get him to do anything.”

Trending

Dan died by suicide on April 29. The week before, Chris took his dad to the Tyler Centennial Veterans Affairs Outpatient Clinic on three occasions. Each time, healthcare workers made unfulfilled promises, he said.

Better healthcare could have saved Dan’s life, his family said.

Frustrations and failures

Nationwide, veterans express concerns regarding the quality of care provided by Department of Veterans Affairs VA facilities. Recent investigations by nationwide nonprofit news outlet ProPublica showed the VA failed to provide adequate treatment for veterans struggling with mental health issues.

Veterans often have to wait for appointments, but for people like Dan, the need for care is urgent. While they wait, their symptoms may get worse. In addition to his mental battles, Dan was suffering from numbness, constipation and heat sensitivity.

“To a person with a mental illness, two weeks is two years,” Chris said. “That’s two weeks of pacing. That’s two weeks of not sleeping. That’s two weeks of him not eating, not going to the bathroom.”

Trending

Chris took Dan to the Tyler VA clinic on April 16, two weeks before his death, for a mental health check and bloodwork. Chris said the staff showed little concern. The next day, Dan visited the clinic again before going to a local emergency room , where he was prescribed medication to treat his constipation. He went back to the VA clinic one day later and got normal lab results – and no further help, Chris said.

On April 22, Chris said he took his dad back to the VA clinic and pleaded with staff for Dan to see a mental health doctor. He said an employee told them there wasn’t a doctor available and Dan could see a nurse instead.

“My dad is behind me … and you can see him falling apart. I’m like, ‘Dad, we are going to get you in there,’” Chris said.

Still waiting to see a doctor, Dan broke down and shared critical passwords and information with his son, telling him he felt there was no other escape but to end his life. Chris approached the front desk and insisted his dad see a doctor as soon as possible.

A nurse then performed an assessment, and Dan was scheduled for a Zoom call with a psychiatrist that day.

Back in the waiting room, a doctor who’d seen Dan before approached Chris and Dan and asked what was happening. Chris said his dad responded that he wasn’t doing well, and the doctor replied, “You should have called me.”

“My dad goes, ‘I did. I called your number. You said you’d always answer, and you didn’t answer,’” Chris said. “Well, there goes his trust.”

Chris again asked clinic staff for his father to be seen, and the doctor promised him an appointment with his doctor that day. While waiting for Dan’s virtual visit, they went outside for some fresh air.

When they returned, a nurse informed them they had missed their appointment because staff had called their name, but no one was there.

“We’re here for mental health. (If) they don’t see you, go look outside. Send an officer. ‘Hey, I have a mental health patient here that I can’t find.’ That should be a priority,” Chris said. “You guys promised me a doctor.”

Chris became upset when the nurse informed him his father was considered low-risk, and once again, Chris insisted on seeing a doctor. Eventually, the first doctor who had promised to help came out and assisted Dan in briefly meeting with another doctor, who then prescribed Dan an antidepressant.

He informed the doctor his father had suicidal thoughts and ideation and sought further guidance. The doctor told Dan to wait for the medicine to work but had no additional advice, Chris said.

According to the National Institute of Mental Health, antidepressants take four to eight weeks before any improvements may be seen.

“They told him [to wait] four to six weeks to see results, and when I told them he won’t be in that chair in four to six weeks, they said, ‘It is what it is,’” Chris said. “My dad is just defeated.”

Care challenges

Chris isn’t the only East Texan concerned about the quality of care offered by the Tyler VA clinic.

Charlie George married a Marine and knows all too well the pain that comes from losing a loved one to suicide. After her husband’s death, George dedicated herself to supporting other military families grappling with similar losses – and raising awareness of the mental health struggles veterans face.

Veterans tell George stories of their difficulties in trying to get care from the VA. These include issues such as long wait times and poor communication that often leave veterans confused and frustrated.

The quality and timeliness of VA healthcare have faced scrutiny throughout the past decade. In 2014, an investigation revealed that about three dozen veterans died awaiting care at a clinic in Phoenix, Arizona, and problematic appointment scheduling affected veterans across the nation.

Many veterans who call the Tyler VA clinic are rerouted to other facilities, such as the clinic in Dallas – if their calls are answered at all, George said.

“Communication … between Dallas, Tyler and the veteran himself is horrific,” George said. “The right hand doesn’t know what the left hand is doing.”

Communication issues often cause misunderstandings and missed appointments for veterans.

Getting appointments by phone can be tough for veterans, especially for those experiencing homelessness who might not reliably be able to receive phone calls. Others call the clinic for days without receiving an answer or miss call-backs because they don’t answer calls from numbers they don’t recognize.

Many older veterans would benefit from receiving appointment reminders in the mail rather than via phone calls, according to George, because they come from a generation less accustomed to using phones.

“These guys are not going to sit there and call all day long, or every day for a week,” George said. “Those are the ones that I am … hearing all the time: ‘I called for a week. I tried to set something up, and they scheduled me two months out, and we can’t wait two months.’”

Through the VA’s community care network, veterans are have access to healthcare from providers outside the VA if the agency can’t schedule an appointment for the veteran at a facility within a 30-minute average drive from the patient’s home or within the next 20 days.

Even in cities with many healthcare options, it can take weeks for civilians to get appointments. When veterans seek care elsewhere, it can add to the delays in treatment, George said.

The Tyler VA clinic also has a hard time retaining doctors, according to George. A veteran told her his doctor left because things were “chaotic.” New doctors mean veterans have to tell their whole story again, which can be upsetting for some of them.

“They’re different every time,” George said. “I know that’s going to happen on occasion, but this is a consistent problem that they do not have the same doctor.”

VA Clinic Director Lehebron Farr said in an October interview with the Tyler Morning Telegraph that East Texas has been a challenging area to recruit quality applicants. Doctors leave the Tyler clinic for opportunities in bigger cities. Some come from out of state, work for a couple of years and then decide Tyler’s not right for them.

“They leave for areas that are more advantageous to their families,” Farr said. “It’s just something that happens, and people make those moves for their own personal reasons.”

The clinic offers relocation and retention incentives, recruitment awards and educational benefits along with increased market pay to attract prospective providers, Farr said.

Farr said staffing challenges at the clinic are attributed to its rapid growth.

“Moving into this larger facility and getting the amount of patients that are coming on has been challenging, and so the adding of those new positions is not because somebody has left. It’s adding to what we already have,” Farr said.

In an October interview, Farr said at the time, the clinic had 6.5 providers serving 7,700 veterans, along with two virtual or telehealth providers. He said an ideal provider-to-patient ratio is one full-time provider per 900 to 1,000 patients, with providers seeing eight to 13 patients daily when fully staffed.

In a statement to the Tyler Morning Telegraph in May, Jeffrey Clapper, public affairs officer for the VA North Texas Health Care System, said the Tyler VA has seven Patient Aligned Care Teams (PACT) providing primary care to 8,117 patients.

These PACT teams include a primary care provider, clinical pharmacist, registered nurse care manager, licensed practical nurse or medical assistant and a clerk. For other services, they can call on social workers and specialists.

To address the increase in demand for care, during the past six months, staffing was increased at the Tyler VA clinic with the hiring of a mental health nurse, a mental health advanced practice registered nurse, a psychiatrist and the addition of two primary care virtual positions.

Chris said even though his dad was assigned a primary care doctor when they moved to East Texas in September 2023, Dan wasn’t scheduled to see the doctor until May 3. Chris also said he didn’t know about community care or other options for his dad.

Personal struggles

A chief petty officer, Dan once repaired electrical systems on naval ships. He retired with honors to focus on raising his son; he was a single father after his wife died.

“He loved his time in the military,” Chris said. “That is probably when he was most happy outside of when I was born.”

Dan raised his son with a military-like structure, instilling discipline, responsibility and resilience.

“I never needed anything. I never wanted for anything. … It was very strict, but I wouldn’t want it any other way,” Chris said. “If I had to choose being raised the way I was or the way that a lot of kids are raised nowadays, I would have chosen the way I was raised.”

Dan was a craftsman who built the family’s childhood home and personalized his house in East Texas. He built everything with his own “blood, sweat and tears,” Chris said. His passion for classic cars was matched only by his love for following his son’s baseball career.

But Dan was not without his flaws. His meticulous organization and selective nature extended to the people he allowed into his life. Dan quickly removed himself from people’s company when someone failed to meet his standards or betrayed his trust.

Chris described his dad as a nice guy, but said he wasn’t the type to ask for help. He spent a lot of time by himself and didn’t have a social network of friends. If Dan would’ve had a strong advocate to help him get quality care, navigate the VA system and connect with veteran support groups, he might still be here today, Chris said.

In September 2023, Dan moved to East Texas to be closer to Chris. At first, he stayed with Chris and his wife, Mallory. During that time, Dan pitched in by mowing the lawn and having late-night or early-morning chats over coffee with Mallory. He did whatever he could to lend a hand to his family.

In November, he moved into his own home. He soon started experiencing intense heat sensitivity and physical symptoms. By February, Chris noticed a decline in his father’s mental health.

“He was fine here, happy as can be, helping us with anything without even being told. I didn’t even have to ask, and then now, I’d have to beg him to come to his appointment,” Chris recalled. “Whatever changed in his chemical system … happened at his time of being in that home.”

Chris remembered a phone call when Dan told him he was feeling down about life. Hoping to cheer him up, Chris suggested they build a pitching machine stand together – a type of thing they usually liked doing – but his dad didn’t seem into it.

“We talked on the phone, and he told me how much he hated it here,” Chris said. “I really knew something’s wrong when he didn’t try to help me. … There’s never been a time where he wouldn’t help me.”

Dan was fixated on setbacks in his personal projects, viewing them as failures. His house and workshop were set up, except for the gutters. He had the dirt redone a couple of times but wasn’t happy with how it turned out, Chris said.

To most people, it might seem like no big deal – just putting on gutters and letting the grass grow around his new house. But every time he tried to seed it, heavy rains washed away all the dirt work he’d done.

It made him feel like he was failing at everything. It wasn’t that he couldn’t afford it; he had plenty of money, Chris said. The issue was feeling like he was wasting it. He couldn’t stop fixating on those few things that weren’t just right.

“Those things, in my non-medical professional opinion, were magnified because of the depression,” Chris said. “It felt like the world was ending when he didn’t get it right.”

Knowing his dad didn’t have many people to lean on, Chris offered to help and even brought in his friends, but it didn’t make Dan feel any better.

“The list was so big in his mind,” Chris said. “He just didn’t even want to start. It just seemed so insurmountable, obviously in his head, with the ending. I think mental health and physical health, as we all know, go hand in hand. When you feel worse, you start getting worse.”

The VA clinic staff basically said, “It is what it is,” according to Chris, and admitted they didn’t know what else to do. They recommended Chris take Dan to the Dallas VA clinic if they weren’t happy with the care in Tyler.

By the time the Tyler VA prescribed an antidepressant, Dan felt defeated. Having been promised treatment and support, Dan’s trust in the clinic was gone, Chris said.

“If my dad was here by himself, in his mental state … Who would have his back?” Chris said. “I would hate for any veteran to go through this.”

Despite pleading for assistance, Dan was never referred to outside resources.

“I firmly believe that if there was a plan and a light at the end of the tunnel, my dad would be here right now,” Chris said. “That’s the way they’re going to go if you give them no way out.”

In a statement to the Tyler Morning Telegraph regarding Dan’s suicide, officials with Office of Public and Intergovernmental Affairs for the VA said, “We are deeply saddened by this news and send our heartfelt condolences to the family and friends impacted.”

Moving forward, Chris said he is becoming an advocate for veterans and aims to raise awareness about veterans’ mental health and suicide prevention – an effort that could have made a difference in Dan’s story.

“They don’t have the tenacity (to sort through the confusion), and if they don’t have a (spouse) that’s going to stand firm and push for him or a mom or somebody that’s going to advocate for them, then it’s just not going to get done,” George said. “Chris was trying to advocate but just didn’t know the resources.”

Resources to help

Preventing veteran suicide is a goal of numerous organizations throughout East Texas.

Some veteran advocates say veterans aren’t aware of the help available to them – or well-meaning people have misinformed them about what help they can and can’t access, said Joy Lowe, veteran suicide prevention outreach coordinator for the East Texas Veterans Resource Center.

Since January 2023, under the COMPACT Act, veterans in a suicidal crisis can go to any VA or community healthcare facility to receive free emergency health care, including ambulance transportation costs.

Veterans are also eligible for inpatient or crisis residential care for up to 30 days and outpatient care for up to 90 days, including social work. Extensions may be provided if the person remains in an acute suicidal crisis.

The Mobile Crisis Outreach Team from the Andrews Center, a mental health service in Smith County, is available 24/7 to help people in mental health crises. This team of professionals meets with individuals in clinics and the community to provide immediate assistance.

The outreach team helps those who are at risk of harming themselves or others or who are facing severe mental or physical decline, and offers a range of services, including emergency care, in-patient hospitalization, urgent care, crisis follow-up, relapse prevention and connection to community resources. For help, call the crisis hotline at 877-934-2131.

The East Texas Veterans Resource Center, with locations in Longview and Texarkana, aims to fill information gaps, Lowe said. The center is a partner agency with the VA and is a program of Community Healthcore, the authority overseeing mental healthcare in the region.

Veterans can find the latest information about services they might need, including financial assistance, mental healthcare providers, peer support groups, veteran-specific employment programs, disability and VA benefit enrollment assistance and more at the resource center

“What we’re trying to do is to get that information out and let them know that there’s a lot more resources,” Lowe said.

Lowe oversees the center’s Staff Sergeant Parker Gordon Fox Suicide Prevention Grant Program, which serves veterans in 16 Northeast Texas counties. Veterans can enroll in the therapy program and access VA mental health care even if they don’t qualify for any VA care.

It’s also open to veterans’ family members, although they wouldn’t receive care through the VA.

“We don’t just help veterans. We help their families as well,” Lowe said. “The family is going through whatever the veteran’s going through.”

Even though resources are available for veterans, many don’t take advantage of them, Lowe said.

Misinformation can keep veterans from seeking the help they need. In some cases, they’ve been given incorrect information by friends or fellow veterans, Lowe said.

She recalled an instance where a veteran told her he thought he couldn’t seek disability benefits until he turned 65 because a friend told him so.

“That’s where we come in,” Lowe said. “We want to let them know.”

Some veterans might struggle with survivor’s guilt that keeps them from seeking help, while others might feel scared or ashamed about talking about their struggles.

“When you’re in the military, there is a stigma with mental health,” Lowe said. “They get so used to stuffing it down that they just continue to do that throughout life. Well, eventually, that’s all going to come out somewhere.”

Veterans often respond best to other veterans in crisis because they share similar experiences and challenges. This bond can be crucial for effective support during tough times, George said.

“When you have a veteran who’s walked it with you, been boots-on-the-ground where you’ve been, and who now can help you through that, they’re more apt to open up to them because they understand,” George said.

The East Texas veterans community is large, with many members offering their contact information to others in crisis.

Despite misconceptions about the Veterans of Foreign War as a bar scene, the organization strives to offer community service and create a family-friendly environment, Veterans of Foreign Wars Post No. 1799 Chaplain Mike Howk said. People are encouraged to come in and enjoy camaraderie among veterans.

Howk and retired Marine April Scarborough, owner of Starbrite Therapeutic Equestrian Center urge veterans to personally reach out if they need someone who understands and will listen.

Howk can be reached at 430-435-4183 and Scarborough at 903-530-4050.

The resource center isn’t a counseling service, but it does connect veterans with those entities and people who understand what they’re going through, said Lowe, a U.S. Air Force veteran.

“I know what it’s like to be in a dark situation and think that there’s no way to come out of it,” Lowe said. “I’m living proof that it’s possible to go through something and come out on the other side. So, a lot of times, it’s about making a connection with somebody.”

Veterans can use the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline to contact the Veterans Crisis Line by dialing 988 and pressing 1, or dial 2-1-1 to find information about local resources.

- The Mobile Crisis Outreach Team from the Andrews Center is available 24/7. For help, call the crisis hotline at 877-934-2131.

- To contact the East Texas Veterans Resource Center, call 903-291-1155 or visit www.helpforvets.com. The resource center is in the Community Connections building at 501 Pine Tree Rd. in Longview and is open Monday through Friday from 8 a.m. to 5 p.m.

- By dialing 988 and pressing 1, veterans can use the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline to contact the Veterans Crisis Line or dial 2-1-1 to find information about local resources.

- Retired Marine April Scarborough, Starbrite Therapeutic Equestrian Center owner, can be reached at 903-530-4050.

- VFW Carl Webb Post No. 1799 Chaplain Mike Howk can be reached at 430-435-4183.

- The VA operates the nationwide Veterans Crisis Line, which serves veterans even if they aren’t enrolled in VA care. It can be reached by calling 988 and dialing 1. It’s also available by texting 838255.

- People in immediate danger of self-harm or danger to others should call 911.