‘Bookends of deception’: Texas court opinion details holes in murder case, grants innocence for Kerry Max Cook

Published 3:59 pm Thursday, June 20, 2024

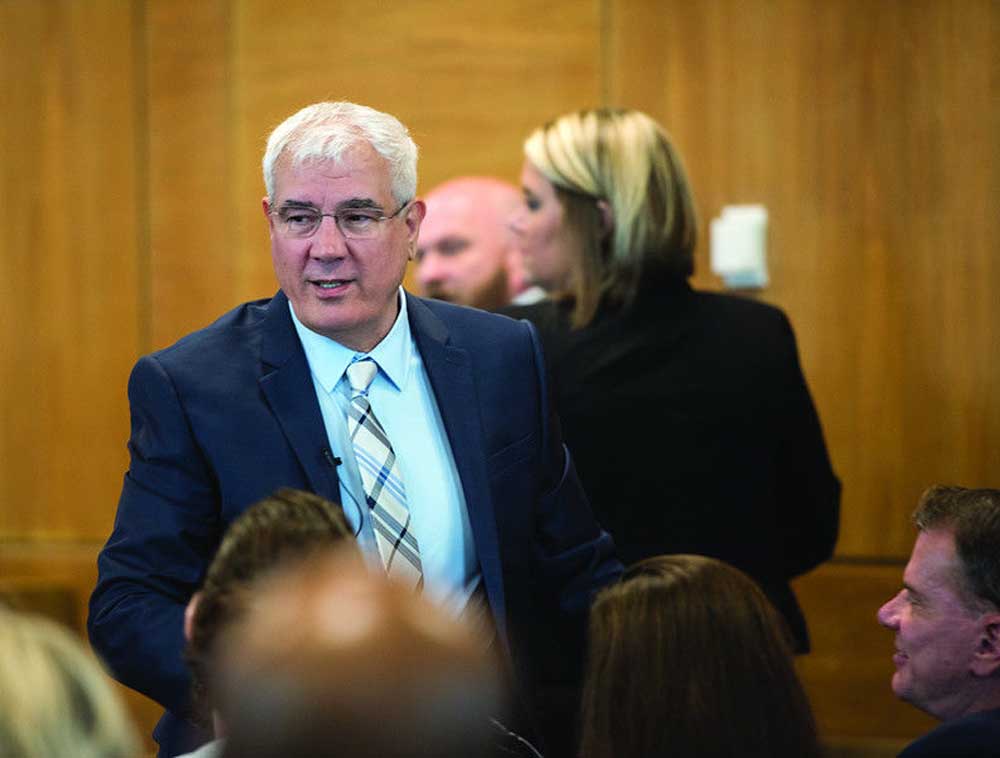

- Kerry Max Cook talks to family members in the Smith County 114th District Court in 2016. This week, Smith County moved to dismiss all charges and the indictment against him in a 1977 crime he didn’t commit. (Tyler Morning Telegraph File)

Linda Jo Edwards was brutally murdered on June 10, 1977 in what a judge called one of the most notable murder cases of the last half-century. Forty-seven years later, who killed the 21-year-old Tyler woman remains unknown.

Early that morning in June 1977, Edwards was found dead in her bedroom at a Tyler apartment complex on Old Bullard Road.

Kerry Max Cook, a former Jacksonville resident, was accused in the crime after his fingerprint was found on Edwards’ patio door. However, he maintained another man — James Mayfield, with whom Edwards was having an affair — was responsible for the crime.

News stunned the Tyler area and beyond Wednesday when the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals ruled Cook is innocent. The ruling cites allegations of prosecutorial misconduct that led to Cook spending 20 years on death row for the crime he didn’t commit.

“Marked by bookends of deception spanning over 40 years, this case has traversed a winding odyssey through our justice system stretching back to 1977,” Judge Bert Richardson wrote in the opinion.

The legal odyssey includes three trials, multiple appeals and reversals before the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals and the U.S. Supreme Court, followed by a plea agreement of no contest on the verge of a fourth trial in 1999.

The deception begins, Richardson wrote, where the state failed to disclose and was not truthful to the defense, court and jury about a favorable deal given to a “jailhouse snitch who was their star witness” in Cook’s first trial. This fact wasn’t revealed to Cook until 14 years after the testimony, the ruling states.

The inmate Edward “Shyster” Scott Jackson was 22 at the time and had been indicted on a first-degree murder charge. He testified he met Cook in jail in August 1977, when he said Cook told him Cook confessed to him specifically how he had killed Edwards. Jackson later admitted in a 1978 interview with the Dallas Morning News and a Texas Ranger, and again at Cook’s pre-trial writ hearing in 1992, that his testimony was a total fabrication.

“I lied on him to save myself,” Jackson said, according to the ruling.

“Marking the other end of this 40-year odyssey,” Richardson writes the alternate suspect, Mayfield, admitted in a 2016 sworn deposition, under a grant of immunity, that he lied about the timing of his last sexual encounter with Edwards.

“In doing so, (Mayfield) admitted to perjuring himself in front of multiple juries and at pretrial hearings,” Richardson wrote.

Now formally exonerated, the ruling is one Cook has been chasing for decades.

“This case is riddled with allegations of state misconduct that warrant setting aside (Cook’s) conviction,” Richardson wrote. “And when it comes to solid support for actual innocence, this case contains it all — uncontroverted Brady violations, proof of false testimony, admissions of perjury, and new scientific evidence.”

The ruling states Cook’s actual innocence was decided in light of new evidence which includes DNA evidence of Mayfield’s sperm in Edwards’ underwear from the night of the murder, along with evidence of false testimony and state misconduct. Richardson writes this all amounts to “affirmative evidence that unquestionably establishes (Cook’s) innocence.” The court holds that “no rational jury would convict (Cook) in light of the new evidence.”

Multiple other reasons for the innocence are explained by the court in the 106-page document, including weaknesses in the state’s timeline of events. According to the ruling, those include: “The numerous inconsistencies with Paula Rudolph’s (Edwards’ roommate) eyewitness testimony by itself and its incompatibilities with other evidence; Cook’s fingerprints on the sliding patio door, the state’s deception regarding their age, and other exculpatory inconsistencies surrounding them; problems with the state’s crime classification and criminal profile generated from the crime scene as applied to Cook; the missing hair with a bloody root found stuck to the victim’s buttocks; inconsistencies in Bob Wickham’s (former sheriff’s deputy) testimony of Cook’s alleged confession; and Mayfield’s semen DNA in the victim’s underwear, Mayfield’s 2016 deposition, and his knowledge of ‘The Sexual Criminal’ by J. Paul de River and its context to the murder. (This includes his admissions of perjury over multiple trials spanning decades.)”

A number of “suspicious and troubling elements” to the case were largely ignored, according to the ruling, including the fact that a number of witnesses had to be given immunity in exchange for their testimonies.

The court states Cook’s 20 years on death row were “torturous” and that he has met the burden required for actual innocence, and therefore relief was granted. Cook has maintained his innocence throughout the last nearly half-century and the court calls him a “victim of numerous Brady violations, secret deals, prosecutorial blunders, and perjured testimony.”

The opinion also states Edwards deserves justice for her murder “and for the unspeakable way it was committed.” She had been beaten in the head with a plaster statue, stabbed in the throat, chest and back more than 25 times and sexually mutilated, according to previous reporting by the Tyler Morning Telegraph.

“It is alarming that for more than four decades some of those charged with pursuing that justice for Linda have actually obstructed the search for the truth of what really happened that night,” Richardson write.

Richardson notes that in these 40-plus years, memories have faded, witnesses have died and evidence “in the care of the state has been inexplicably destroyed.”

“Linda Jo Edwards deserves better,” he wrote.

More about the case

June 10, 1977: Linda Jo Edwards, 21, was found dead in her bedroom at a Tyler apartment complex on Old Bullard Road. Cook was accused in the crime after his fingerprint was found on Edwards’ patio door. However, he maintained another man was responsible for the crime.

1978: During his trial, Cook invoked the Fifth Amendment and did not testify. He did so again in a 1992 retrial, a 1994 retrial and a 1999 grand jury investigation. Also in 1978, Cook was tried for the crime, convicted and sentenced to die by a Smith County jury.

1989: The Court of Criminal Appeals overturned the case in 1989, because a psychologist had not read Cook his Miranda warning, thus rendering all information in the psychological interview useless. He was not freed at the time because he remained under indictment for capital murder, and then-Smith County District Attorney Jack Skeen took two more tries at convicting Cook.

1992: Smith County tried the case, but the jury deadlocked and a mistrial was declared.

1994: Cook was found guilty of capital murder, but prosecutors used the testimony of a witness who had died.

1997: The Court of Criminal Appeals reversed the 1994 verdict.

1998: As Smith County was moving forward with a fourth trial, Skeen offered Cook a deal that would convict him of murder but would not require him to admit he killed Edwards. In exchange for his plea of no contest, Cook was convicted of murder but sentenced to the time he already served.

1999: Cook was released from prison, then spent decades seeking a full exoneration.

2016: A state district judge set aside Cook’s conviction after another suspect, James Mayfield, admitted to previously giving false testimony about when his affair with Edwards ended. However, visiting Judge Jack Carter, of Texarkana, declined to recommend the state Court of Criminal Appeals approve Cook’s writ of actual innocence.

2024: Cook is formally exonerated on June 19 by the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals