Book World: Robert Kennedy’s path from son of privilege to civil rights advocate

Published 11:21 pm Tuesday, July 6, 2021

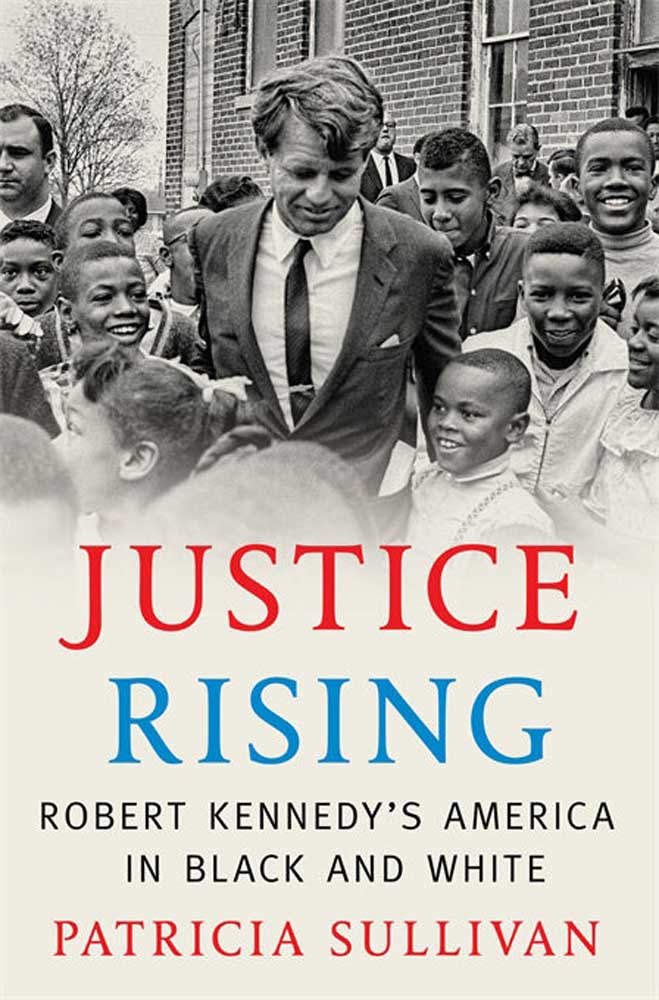

- Justice Rising: Robert Kennedy’s America in Black and White

Justice Rising: Robert Kennedy’s America in Black and White

By Patricia Sullivan

Belknap. 515 pp. $39.95

– — –

In most accounts of the tumultuous 1960s, Robert Kennedy plays a supporting role. He was President John F. Kennedy’s younger brother. His work as attorney general in the Kennedy administration is seen as supporting the president’s agenda. His campaign for the presidency in 1968 is often framed as promising the continuation of the Kennedy legacy. Even his violent death that year is typically mentioned as one of a trio, overshadowed by his brother’s assassination and the aura of conspiracy that surrounds it and by the murder of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., with its profound implications for race relations and effect on the civil rights movement.

In “Justice Rising: Robert Kennedy’s America in Black and White,” Patricia Sullivan corrects this and puts Robert Kennedy near the center of the nation’s struggle for racial justice. She offers a moving and enlightening account of a life of public service marked by ambition and marred by serious errors in judgment, but more than redeemed by a sincere, powerful and enduring commitment to social justice. Kennedy was a political insider who became a fierce critic of the status quo; a son of privilege who came to sympathize deeply with the least fortunate. Sullivan describes how Kennedy grew from an idealistic but naive young man into a passionate and sophisticated advocate for racial justice. Near the beginning of the book, Kennedy is shocked and bewildered when a civil rights activist says he would not willingly defend his country in wartime. Near the end, Kennedy berates White college students who sought draft deferrals for themselves but were indifferent to the plight of the Black servicemen who took their places on the front lines.

Sullivan reminds us that many civil rights activists were initially skeptical of Kennedy. Some never forgave him for taking a job on the staff of the Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations, chaired by the red-baiting senator, Joseph McCarthy.Kennedy later acknowledged that working for McCarthy was “wrong.”

Sullivan recounts a remarkable meeting in 1963 where Kennedy hosted the essayist and novelist James Baldwin, the actress Lena Horne, the playwright Lorraine Hansberry, the singer Harry Belafonte, the sociologist Kenneth Clark, and a member of the Congress for Racial Equality, Jerome Smith. Kennedy did not impress the group: At one point Hansberry lamented that “you and your brother represent the best a white America has to offer. If you’re insensitive, there’s no alternative to the streets and chaos.” Later, Baldwin joined other progressives such as Paul Newman and Gore Vidal in backing Kennedy’s Republican rival Kenneth Keating in the Senate election of 1964.

Kennedy grappled with the violence surrounding the civil rights struggle in the Jim Crow South, and he worked to understand the distinctive indignities and deprivation of Black life in Northern cities. As attorney general, he developed the Kennedy White House’s positions on civil rights and the nation’s response to the recalcitrance of Southern politicians bent on maintaining segregation. His efforts both shaped the civil rights legislation of the 1960s and helped to make it law. He was a powerful advocate for racial justice, both in office and on the campaign trail as he ran for senator and later for president. After the Watts uprising in 1965, while President Lyndon Johnson compared Black “looters” to “the night riders of the Ku Klux Klan,” Kennedy insisted that “just saying ‘obey the law’ is not going to work. … We have a long way to go before the law means the same to a Negro as it does to us.”

Kennedy became a trusted ally of the civil rights movement and one of the most popular and effective politicians of his day. Sullivan notes that civil rights leader (and later congressman) John Lewis remarked that after King was assassinated, “I transferred all the loyalty I had left from Dr. King to Bobby Kennedy.” Instead of pandering to bigots, Kennedy insisted that Black lives matter. He challenged the nation to reject “the vanity of our false distinctions among men. Our own children’s future cannot be built on the misfortune of others.” He chastised White voters who opposed social welfare programs and civil rights, often alienating them. Campaign strategists today would consider such language political suicide. Yet despite — or perhaps because of — this moral courage, Kennedy was poised to win the Democratic nomination and the presidency when he was fatally shot in Los Angeles in 1968.

“Justice Rising” ends on a plaintive note, inviting us to wonder what might have been had Kennedy lived to beat Richard Nixon, whose punitive “law and order” politics metastasized to become today’s crisis of mass incarceration and abusive policing. In the decades after Kennedy’s death, examples of inspiring political leadership have been rare, overshadowed by a pervasive atmosphere of corruption, cynicism and incompetence. But alongside a profound sense of loss, the book also contains a hint of optimism in chronicling a moment when this nation came close to fulfilling its promise. Kennedy’s personal growth and his political triumphs are reminders of the transformative potential of American democracy.

Richard Thompson Ford is a professor of law at Stanford. His latest book is “Dress Codes: How the Laws of Fashion Made History.”