Losing much of her sight was terrifying, but it gave Megan Dodd the vision she needed to help others

Published 10:37 pm Sunday, March 13, 2016

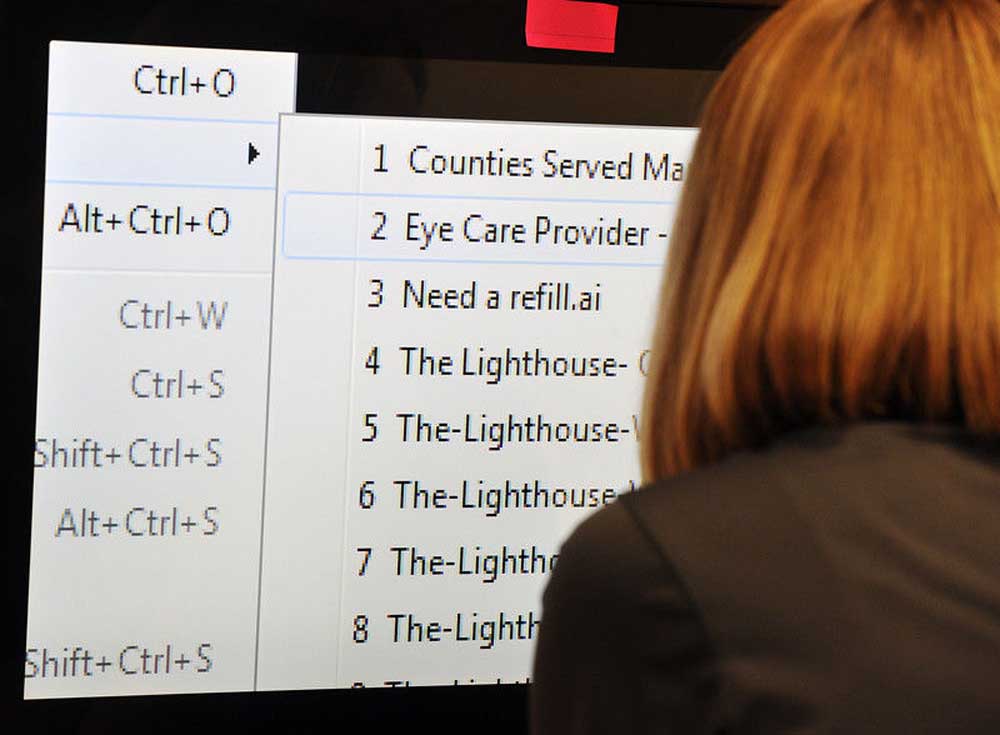

- Adaptive software lets Megan Dodd zoom in tight on sections of her computer monitor on Wednesday, Jan. 27, 2016, in her office at the Lighthouse for the Blind in Tyler. Ms. Dodd, who is legally blind due to a genetic condition that leads to scarring on the retina of her eyes, works as a community outreach representative for the agency. Andrew D. Brosig/Tyler Morning Telegraph

The young woman in the driver’s seat is wearing large bottle-cap glasses with a black rectangular contraption connected to the top of the frame. Her blue eyes are magnified behind the thick glass. She stares intently at the road, slightly lowering her chin to look through the top of the black box every few moments.

She is smiling as she describes the restrictions on her license. “I can’t go over 45 mph, and can’t drive during the night.”

Megan Dodd is 27 years old, legally blind and has been driving since March of 2015.

Using a Bioptic, a pair of eyeglasses with a magnifier mounted on top, she is able to drive like a person with no vision impairment.

She continues smiling as she slows to stop at a red light.

“I am a very independent person and I get very frustrated if I feel that I am limited in any way,” Dodd said. “I would absolutely guarantee I am on par with any sighted person on what I am capable of doing.”

DIAGNOSIS

Dodd began losing her vision when she was 18.

“When I was in college, I was studying a lot and started noticing these lights in my eye,” she said. “I thought it was eye fatigue because I was studying a lot. Lights in my eyes started to form into a circle … and then it filled into this blind spot right in the center of my vision.”

She was diagnosed with Stargardt’s macular dystrophy (SMD), an inherited disease that causes light-sensitive cells in the retina to deteriorate, particularly where fine focusing occurs.

“The way my eye works is there is scar tissue there now,” Dodd said. “If you cut my eye in half and look at the horizon of the eye there is scarring right there in the center and that creates those lights and that blind spot.”

With only peripheral vision, she has trouble recognizing faces, seeing small things and reading regular print.

“I can see the stuff on the wall, I can see my desk, I can see the stuff on the desk but then there is a blob of light right in the center of my vision. … I have a lot of usable vision. I can get around, I look sighted and I come across as sighted. There are a lot of people who have vision loss and they blend into the world and make do with what they can see and just fake the rest.”

LOSING SIGHT

Dodd was attending Texas Tech University when her vision loss started affecting her daily life.

“As I was losing my vision it was taking longer and longer for me to read while I was still trying to read with just my eyesight. It was taking an hour a page, so on one textbook page I would spend an hour trying to read it and take notes on it too. If you have to read 100 pages a night, it is just impossible.”

She returned to East Texas to attend The University of Texas at Tyler so her mother could help her study.

“We would sit there and she would read my very boring sociology book,” Dodd said. “That was my solution for a while.”

At the Disability Services office at UT Tyler, counselors suggested she scan the pages of her textbooks into a computer program that reads the text out loud. But that came with problems.

“The software that would read to you was very rudimentary,” Dodd said. “It would mispronounce words, it would pick up really strange things or the scan might not be very good quality. I used that for a while along with some very basic magnifier software.”

After that, Dodd contacted the Texas Department of Assistive and Rehabilitative Services, which provided her with better text reading software.

“They got me some software, but linking up how that software could really help and really put me on the map to allow me to be on par with a sighted person to give me the foundation I needed, that was missing,” Dodd said.

Instead of looking to the agency for additional support and counseling, Dodd tried largely to cope with her vision loss on her own.

“(Most people) go through those processes of grieving and coming to terms with a change and then figuring out how you are going to live with it. I never actually went through those steps. I wanted to deny anything was happening and keep as normal a life as possible.”

NEW OPPORTUNITIES

Dodd graduated from UT Tyler in 2010 with a bachelor’s degree in sociology, minoring in psychology.

“I graduated and then it was like what do I do now? … I hadn’t met anyone that had a disability, never really talked to anyone, so I struggled for a long time. I wasn’t connecting the dots that I need to find someone who has gone through this, or who can at least tell me what to do.”

She then heard about the Lighthouse for the Blind and Horizon Industries in Tyler. The East Texas Lighthouse for the Blind is a nonprofit organization that serves the blind and visually impaired through rehabilitation, education, training and employment. Horizon Industries employs the blind and visually impaired.

At Lighthouse, she was interviewed by the agency’s vice president of operations, who also is legally blind. “It was a really cool opportunity to talk to someone (visually impaired) who was successful and had a stable job, a high level job and was managing this company.”

Dodd was hired as a marketing associate. “I was like, “okay this is big. This is going to open up the opportunity to talk to people who have gone through this.”‘

Dodd has been working at Lighthouse for three years. In 2014, she was not only the Lighthouse’s employee of the year, but also the National Industries for the Blind employee of the year.

“It’s been wonderful to be in an environment that is so positive and supportive and that there is training available and a space to grow.”

MAKING A DIFFERENCE

Dodd recently moved into a community outreach role at Lighthouse. She connects resources with visually impaired individuals who need them.

“I feel like it is an opportunity to share the mission on a bigger scale. I am very passionate about it,” Dodd said.” I love talking to people and connecting to people and I love public speaking.”

Dodd’s mother, Mary Dodd, feels that Megan has found her calling.

“I think Megan has really come through this in such a positive way,” she said. “She’s taken this obstacle and made it something that she can use to help other people, and that’s really her passion – trying to open doors for other people who have visual handicaps so they can have a fulfilling life.”

Because Dodd knows the struggles that come with being visually impaired, she is better able to help others.

“That is what fuels my passion. I want to be able to provide that sense that we are all connected. We all can help each other. If you are struggling with your vision loss we are here to help and want you to be empowered to feel, not like you are having to rely on the services that we offer, but that the services that we offer help you to do what you want. You get the training, you get the equipment, and then you go on and make whatever you want happen.”