Virgil Melton Jr. recalls service as tank commander

Published 10:56 pm Sunday, April 19, 2015

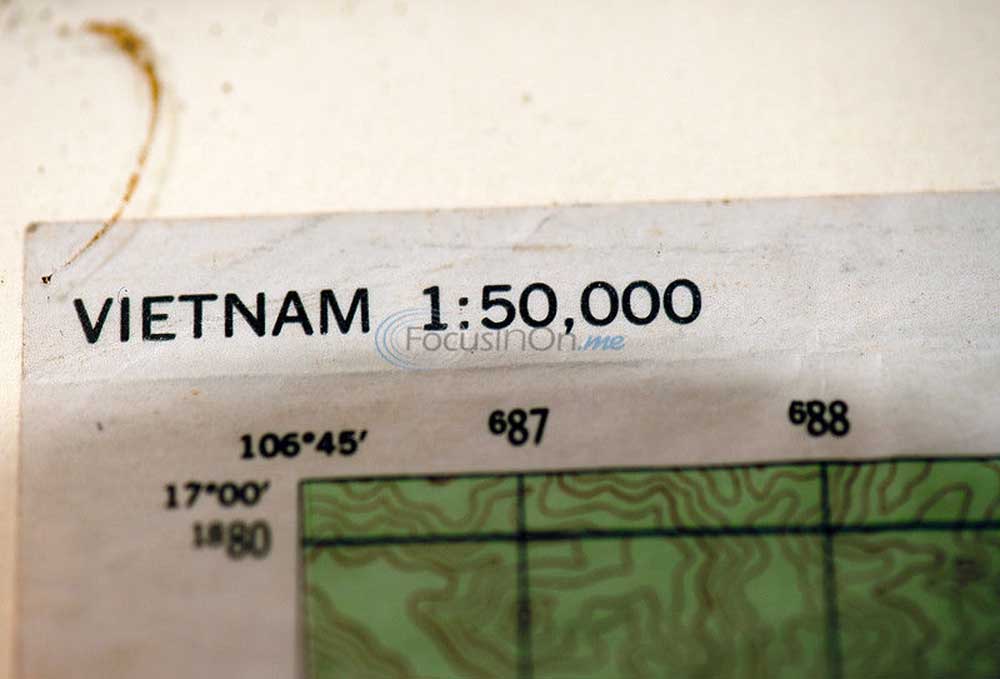

- This framed topographic map of Vietnam was Virgil Melton Jr.'s content companion during his service as a Marine tank commander during the Vietnam War. Photo by Andrew D. Brosig/Tyler Morning Telegraph

Vietnam War Purple Heart recipient Virgil Melton Jr.’s face lights up when he talks about the night 46 years ago when American tanks rolled along the moonlit coastline of the South China Sea and surrounded an enemy camp from atop a sandy ridge.

The former U.S. Marine Corps tank commander remembers the Aug. 15, 1968 incident as if it were yesterday.

Melton, at 19, was leading the caravan of 10 that day, under the command of Capt. R.J. Patterson, a passenger aboard his craft.

About a year earlier, the teen-age Van Zandt County resident was attending Henderson County Junior College, feeling guilty about sitting in class while others were leaving for Vietnam.

When the teenager finally threw up his hands and told his parents he planned to join up, his mother dabbed away tears. His father, a Marine who fought in World War II, gave him a lift to the departure point and a solid handshake for luck.

Within a matter of months, Melton was in a tank in the thick of battle, a world away from the family farm, helping pull off a ’68 sneak attack that is the most vivid of his military career.

As the tanks reached the crest of the ridge, Melton said he was stunned to see an estimated 600 to 800 members of the North Vietnam Army camping below, sandwiched between Americans and the Ben Hai River.

The Vietnamese were unaware they were the intended targets of Operation Lam Son 250.

“We smelled food,” Melton said. “We smelled cooking, we were that close. They were eating breakfast. … We could see their chow lines.”

Enemy fighters spotted the tanks lined along the ridge and began shouting in alarm, sending troops scrambling for cover and weaponry.

“It was a total surprise; they never thought we would go that far in the DMZ (demilitarized zone),” Melton said. “They knew they were caught.”

The tanks began firing, destroying the enemy’s light artillery. They responded, shooting off rocket powered grenades, mortars and machine guns before scattering in all directions, pursued by the Americans.

“We fought from daybreak that morning when we could hardly see, until late that evening,” Melton said. “Then it started getting dark, fast, and we knew we needed to get out of there.”

The tankers tried to make a hasty getaway to safer territory, but two crafts inadvertently rolled over hidden land mines.

One was fixed in a matter of minutes, the other was heavily damaged, requiring a blast of napalm to keep it out of enemy hands, Melton said.

Arriving back at base camp, the intensity of the battle was obvious.

“Our tanks were beat up,” Melton said. “They had mortar damage. They blew the night lights off. There were bullet holes in the tank and rocket fire. We didn’t have a casualty, which was amazing in itself.”

A little of Melton’s luck ran out a few months later when his own tank hit a mine on an unrelated March 28, 1969 search and clear operation.

“It was getting dark,” he said. “There was a creek in front of us. I made a dash toward the creek but the other tanks couldn’t make it. I started up the ridge to join the others.”

The enemy was on the next ridge, and Marines were hunkered down on the hillside.

Melton recalls seeing his best friend, tanker Eddie Miers, blasting away in the direction of the enemy.

“He was lighting them up,” he said. “The barrel of his .30-caliber had turned red.”

Melton was concerned his heavy equipment might roll over the embedded Marines so he bailed out and began walking alongside to help guide it.

“There was a little sandy spot,” he said. “The left front tank track hit a mine. It blew me 30 or 40 feet in the air.”

He doesn’t remember much about the incident, just hazy memories of his men arranging for a medivac ride to the hospital.

Physicians determined he had a blown out ear drum, shrapnel wounds and a concussion.

“The doctors got right on me, surrounding me, checking me out,” he said. “Then one doctor said, ‘You’re going to be all right.'”

Melton spent 35 days in the hospital before he was ordered back to the battlefield.

“I was OK with it,” he said. “I went back to my platoon in mid-May. … I left Vietnam in August of ’69, headed home. I was happy to come home.”

Melton ultimately served 21 months overseas, receiving a Purple Heart and Navy Commendation Medal for valor, the latter of which was awarded because he interrupted a planned grenade attack and saved several crew members.

Melton remembers the day he returned to the family farm, his heart warmed by the delectable smell of his mother’s fried chicken and the familiar slam of the old screen door.

Today, his constant companion in the war — a tattered, rain-soaked map of Vietnam — remains close at hand, framed and displayed in the farm home he shares with his wife, Janice, who calls him her hero.

There are faint scribbles on the map highlighting some of the outposts where he served: Gio Linh, Con Thien, Washout, Charlie 2, Rockpile, Camp Carrol and Cam Lo to name a few.

“Vietnam will take a boy and make a man out of you pretty quick,” he said. “It takes its toll, but that’s what war is about … it’s ugly. We have to understand, if you love your country and you love your freedom, you have to be willing to fight for it.”