65 And Counting: Bass Fishing’s First Soft Plastic Worm Celebrates A Birthday

Published 1:03 am Sunday, June 15, 2014

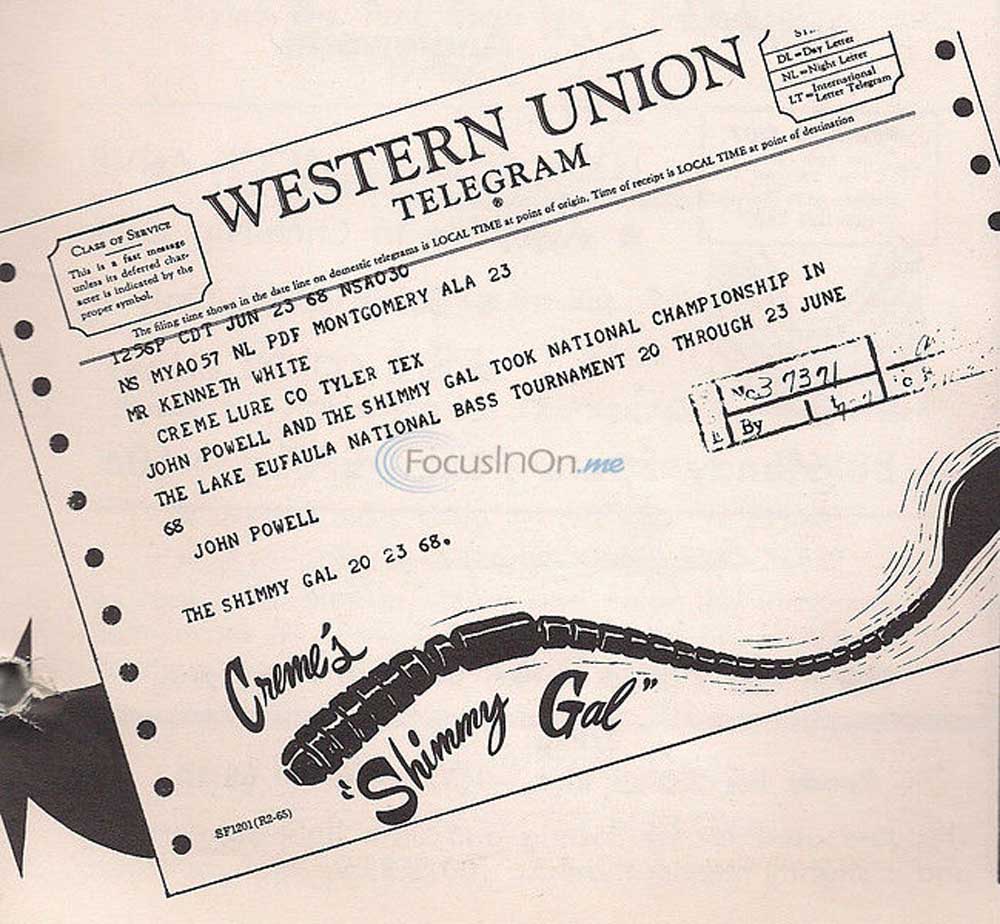

- Courtesy Telegram about Nationa Bassl Champiionship.

Longevity is not something synonymous with the fishing tackle industry. With few exceptions everything introduced yesterday is old news today.

One exception is Creme Lure, the originator of the soft plastic lure, which turned 65 this year.

Trending

Although it got its start in Ohio, Creme Lure and its first worm is more closely associated with Tyler, where it has had its headquarters since 1960. Started by the late Nick and Cosma Creme in their basement, the company has been owned by the Kent family since 1989.

The worm was invented out of necessity and because of a magazine story on opportunities for the future that included realistic artificial fishing worms. Digging earthworms from the frozen ground in winter was a near impossible task in Northern states and while rubber worms and other lures had been around for more than 50 years, they just didn’t perform as advertised.

Working as a machinist in Akron, long the center of the country’s rubber industry and an up-and-coming plastics industry following its discovery during World War II, Creme began working in his basement trying to invent a more life-like plastic lure. He sought advice from chemists at a nearby DuPont plant, but most success of the final product came from trial and error, and a lot of burned up pots and pans, according to reports quoting Mrs. Creme.

Wayne Kent, Creme president, said Creme finished refining his formula and design in 1949, but as a revolutionary fishing product it sunk faster than a boat anchor.

“Little did they know that fishermen would not be so quick to accept this new fake worm,” Kent recalled. “Nick told me many times he had a hard time with the jokes and pranks being used with his worms. Party tricks seemed the perfect place to add his worm to salads and such.”

So the machinist-turned-inventor had to suddenly morph again into a salesman. It was something Creme did well over his tenure as owner of the company.

Trending

To sell the worms to Ohio fishermen Creme rigged them the way they customarily fished nightcrawlers for bass using a harness with two hooks, beads and a small propeller out front.

It took two years to catch the fishermen, but suddenly Creme was headed to the bank selling worms by mail and at area sport shows for five for $1, or about $9 today. They initially came in three colors: natural, black and white.

The early worms, Kent said, looked more like a bolt than an worm. It wasn’t until a few years later when someone actually cast a mold of a real worm that the lure really became lifelike.

The first worm was simply known as the Creme Worm. Along the line it earned the nickname The Wiggle Worm, but officially became the Scoundrel when the company began to produce other models such as the Shimmy Gal and the Shimmy Babe.

Perfect Timing

It is hard to say whether Creme was a business genius or whether his timing was perfect. His introduction of the worm came during what could be called the first heyday of sport bass fishing.

In 1948 Shreveport fisherman Holmes Thurmond introduced the first bass boat. It was made out of modeled plywood with a needle-nose design that led to it eventually being named Skeeter. The two-man boat featured a pair of wooden slats as seats, a transom to hang a small outboard engine and a running light. It was enough to get fishermen on the water and around stump-filled lakes in East Texas and Louisiana.

In 1957 Lowrance introduced the Green Box, the first commercial fish finder.

It was also the dawn of big reservoir construction across the country, including the impounding of Lake Tyler West in 1949 and Lake O’the Pines in 1956. Suddenly fishermen were leaving stock ponds and small lakes for big reservoirs. Once the worms found their way to East Texas they were popular with fishermen.

“Back then we didn’t care what they were doing in Dallas or even Lufkin; it was the reports from the local sports shops that matter, and here it was usually about Lake Tyler,” said Kent, who in the 1950s held a part-time job at Milton Goswick’s Bait and Tackle Shop on East Front Street.

Kent said he remembers a time when he overheard a telephone conversation between Goswick and Cosma Creme.

“He called her long distance, and that was a big thing back then,” Kent recalled. “He asked if they could send more worms down here because of the demand. She told him they couldn’t because they worked through distributors, and that they just didn’t have any because they couldn’t keep up with orders.”

Unwilling to take no for an answer, Goswick asked her if she liked roses. After he got off the phone to Ohio, Goswick called a local rose grower and had two dozen bushes shipped to the Cremes.

“A couple of weeks later several boxes of worms showed up at the shop,” Kent said.

It has been said that those roses, and the strong demand for worms in East Texas, brought the Cremes on a visit to Tyler in the late 1950s. They soon had plans for a second factory on Texas Highway 31 outside the Tyler city limits, and when they returned to East Texas they made it their home.

The original worm worked, but wasn’t perfect for East Texas. The pre-rigged worm had a tendency to hang up on the submerged timber of East Texas lakes. That was good for the manufacturer, which sold more product, but not for the fisherman, who had to replace what was still a commodity.

That changed sometime in the early 1960s with the invention of the Texas rig, something Kent thinks happened on Lake Tyler. The rig, which includes a slip sinker and hook tip embedded in the worm, first appeared in the Creme catalogue as the Rustler in 1964. Allowing the worm to easily slip through grass and not get hung on stumps, the rig instantly caused demand for worms to jump more. At the same time it was the beginning of the end of the popularity of the pre-rigged worm, although it remains in the company’s catalogue today.

Ever the promoter of his product, Creme was revolutionary in forming a pro staff of fishermen around the country who would talk up the product and fish it in tournaments. Two early members of the pro staff were a young Tennessee fisherman named Bill Dance and BASS angler John Powell.

The Creme-Powell partnership was important because it was one of the first angler endorsements, if not the first. Creme reportedly paid Powell $18,000 to fish his worms during the 1967 BASS series.

Kent believes the early worm’s legacy lives on in other time-worn gear used by fishermen today, including rods specifically designed for worm fishing and maybe even casting reels, which in the early days weren’t as popular as spinning reels because of backlashing.

Creme basically had the plastic worm industry to itself until the 1960s, when Flip Tail arrived on the scene with a new look. Not offering design changes quick enough and unwilling to sell in bulk, Creme soon lost its monopoly to a field of competitors that was exploding in size.

Thirty years after Creme’s death, the Scoundrel is still produced in Tyler and still sold to fishermen worldwide. Kent said while the formula isn’t exactly the same as it was in 1949, it is more similar than most fishermen might realize.

Creme died in 1984, but his legacy lives on. Since his death he has been inducted into three halls of fame, the Freshwater Fishing Hall of Fame in Hayward, Wisconsin, the Texas Freshwater Fishing Hall of Fame at the Texas Freshwater Fisheries Center in Athens and the Bass Fishing Hall of Fame in Little Rock.

Have a comment or opinion on this? Email Steve Knight at outdoor@tylerpaper.com, follow him on Facebook at TylerPaper Outdoors and on Twitter @tyleroutdoor.