Vietnam Déjà vu: ‘Donut Dollie’ heads back to war zone and memories

Published 12:03 am Wednesday, May 7, 2014

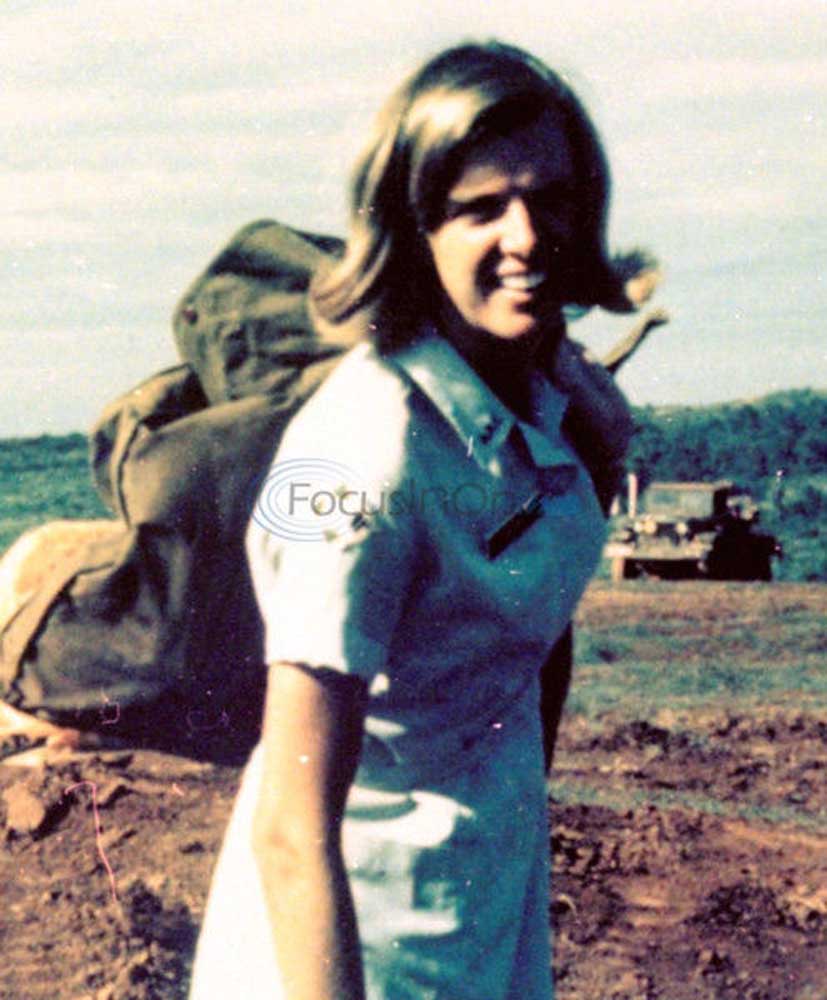

- Courtesy

It was November 1995, and I was on a flight to Saigon. Now called Ho Chi Minh City, although it always will be “Saigon” to me. My upcoming arrival would be within a day of the same date 27 years earlier when I began my one-year tour in Vietnam with the American Red Cross. During the war, the military had asked the Red Cross to recruit young women to provide mobile recreation programs to the American troops in the forward areas of Vietnam. I signed on. My year started in November 1968.

This return trip was arranged by a travel agency as a tour for women who had served during the war. I signed on. Our little tour group had a notable cross section of the female roles in Vietnam — military nurses, USAID civilian nurses, a civil servant who worked in Saigon, an orphanage worker, a flight attendant who flew troops in/out of Vietnam and two Red Cross Girls who still answer to the nickname “Donut Dollie.”

Donut Dollie … a name dating to World War II Red Cross women who drove canteen trucks, served coffee and made doughnuts for the American troops in war-torn Europe. In Vietnam, I had been a Donut Dollie, although we flew in helicopters and never served doughnuts. Now I was returning.

I had a special “side” assignment on this 1995 trip. I was carrying a sealed envelope of U.S. cash to a Vietnamese man, a favor to a retired infantry officer I’d met in Idaho. On his return to Vietnam, he had located a good friend from the war — an artillery officer of the Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN). They had worked together up near the DMZ, doing their best to prevent a takeover of South Vietnam by the North.

When they reunited, the retired U.S. officer found his well-educated friend black-balled from any decent employment in Vietnam society. The country was regimented by the victors of the North, and they did not forgive those who had fought against them.

Consequently, the former South Vietnamese Army officer now pedaled a cyclo (a three-wheeled passenger bicycle) around Da Nang to eke out a living. The Idaho man wanted to get money to him. Wiring funds or sending a check was out of the question. American greenbacks were welcome, but how to get the cash to him? I volunteered to carry the envelope.

I chose to be cautious, not wanting to be observed handing an envelope to a Vietnamese man on a street corner. At a local store that advertised “3 tee-shirts for $10,” I purchased several to use as gifts, then pinned the envelope of money inside one.

The retired U.S. officer corresponded with his friend, who agreed to meet me at the Cham Museum in Da Nang. Upon arrival, I had not yet stepped off the bus with tee shirt in hand when someone said, “Jenny, there is a man here looking for you.” Sure enough, he had a small piece of paper with my name on it. I greeted him, and said, “I have a gift here for you from your friend in Idaho!” Taking his hand I pressed it onto the front of the folded shirt so that he could tell there was something underneath the lettering about Famous Idaho Potatoes. I said, “Feel the quality.” He smiled. My mission was accomplished.

But he had his own mission — one of reciprocation, something to send back to his friend. He introduced me to his wife, who spoke decent English. She pulled out a large pink polyester pillowcase, ruffled on all sides and embroidered with the names and marriage date of the Idaho couple. There were lots of embroidered hearts and birds. It was quite gaudy, but obviously made with gratitude and affection. I praised its “beauty,” assuring them I would personally deliver it. She then caught me completely off guard when she asked, “I make one for you?” I stammered that I wasn’t married, so I had no names or wedding date. I felt badly about saying no thanks and promised I would ask my fellow travelers at lunch if they had an interest.

When the man’s wife showed up at the restaurant, I had to tell her that everyone had admired her work … but unfortunately, no one needed a pillowcase. Now I felt badly again. Not to worry … she then said, “You want a shirt? I make for you.” In a split second I felt “caught,” but I also realized she was desperate to make money. “Okay, but how will we do it? We’re not staying in Da Nang; we’re leaving for Hue after lunch.”

She said she’d take the train up to Hue the next day to deliver the shirt to me at the hotel. I asked how much, and she said “twenty dollars.” I was probably kissing $20 goodbye … but I reminded myself I could spare that amount, especially given the circumstances. Seeing my purse, she said, “No! No money until you get your shirt.” Now that business ethic I liked. We made the deal.

She said she would embroider my shirt with a map of Vietnam, my name, and the dates I was there — 1968-69 and 1995. She asked to take a measurement, and finding a small scrap of paper that had been wrapped around a set of chopsticks, she measured me — shoulders, length, etc., making notes.

As our group boarded the bus, she asked what color I wanted. “Yellow,” I responded.

Our bus negotiated the streets of Da Nang to exit the city and head north to Hue. Not five minutes into the ride, one of the passengers said, “Jenny, look out your window.” Motoring alongside the bus, going our same speed, was a motor scooter carrying two people. The back passenger was my seamstress, holding up two swatches of material — one pale yellow and the other a lot brighter. She wanted to make sure she used my preferred shade. I motioned, pointing to the brighter one. She smiled, and they sped off. “Yes, that’s Vietnam yellow,” I thought to myself.

Did she show up at the hotel as promised? Yes. Did she make the bright yellow shirt with all the special embroidery — name, map, and dates? Yes. I noted that her map of Vietnam, running on the right side of the shirt’s front, now included North Vietnam. I had to remind myself it had become an undivided country. She had marked both Hanoi in the north and Ho Chi Minh City down south. It had “Jenny” and “1968-69” and “1995.” This shirt turned out to be my most precious souvenir of this return to Vietnam. Our small group recognized the extent of the effort and industriousness behind this special yellow shirt.

For me, it also was symbolic. I chose to proudly wear it the day our tour group flew into Hanoi — the headquarters of the enemy decades earlier … now a tourist stop. But I didn’t want to enter Hanoi as an ordinary tourist. Not after 1968-69, and not after having such a special exchange in 1995. I entered the city wearing my new yellow shirt, making my own secret “statement.”

Why did I title this story “Vietnam D←j¢ vu”? — I was measured for another article of clothing in Vietnam in 1969. It was an Air Force Fighter Squadron’s “party” flight suit. Something funny happened, but that is a whole other story, for another day.

A special sign-off here to my brothers in arms… “Welcome Home. You’re Number One.”