Hawking is ancient, dating back about 4,000 years

Published 11:00 pm Sunday, September 1, 2013

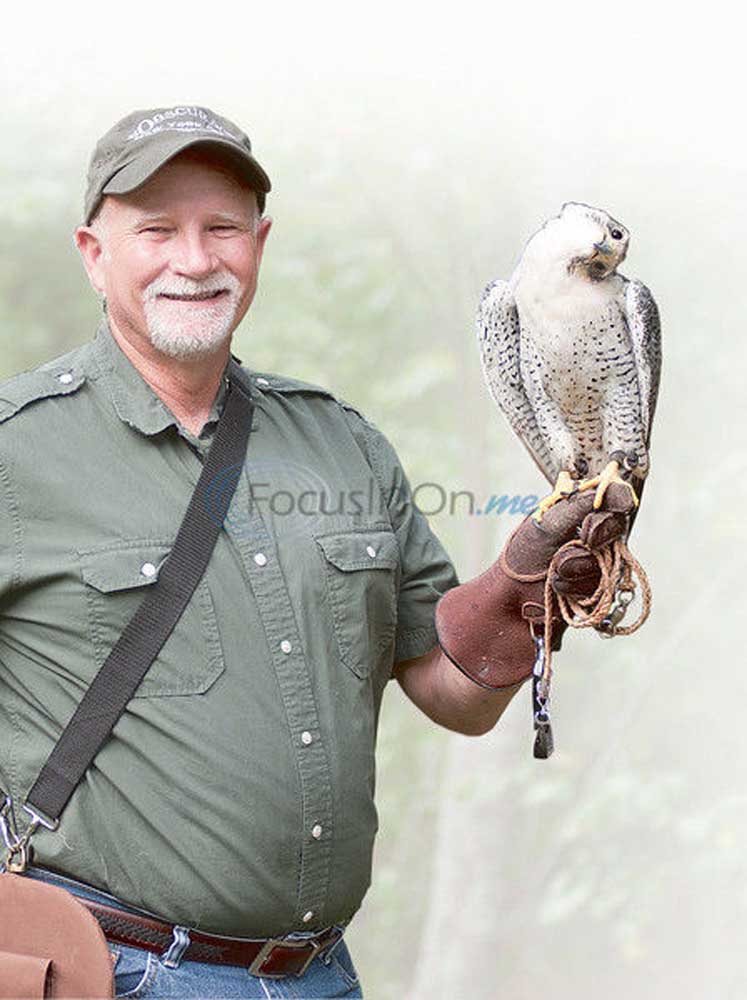

- Danny Pickens, 60, of Whitehouse, is a falconer. He hunts wild game in its natural state and habitat by using a trained bird of prey. Picken’s falcon. Phoenix , is captive bred; he can’t be released into the wild. The bird weighs just under 2 pounds and has a wing span of about 2 feet. Sarah A. Miller/staff

During the summer, Phoenix, a 13-year-old falcon, is used to taking it easy. Duck-hunting season doesn’t begin until November, so he doesn’t make his rounds in the early mornings these days. During this time, he is molting, or shedding old feathers and replacing them with new ones.

Perched on the hand of his owner, Danny Pickens, he begins to “chup” loudly. He doesn’t care to have his picture taken on this day.

Trending

Pickens is a falconer. He hunts wild game in its natural state and habitat by using a trained bird of prey. Phoenix is captive bred—a gyr/peregrine hybrid.

He can’t be released into the wild. The bird weighs just under 2 pounds and has a wing span of about 2 feet.

Captive falcons such as Phoenix typically live a long life—up to 35 years. However, in the wild, they seldom live as long due to predators and injury.

Pickens, 60, has raised Phoenix since he was a chick—less than 15 days old. Since he was so young at the time he came to his owner, the falcon was imprinted on him. In other words, “he thinks he’s people,” as Pickens put it.

He also owns 3-year-old Venus, a 3-year-old anatum peregrine falcon, who is away in a breeding project. The birds are territorial so they are kept separately, in an enclosed structure called a mew.

Pickens has made falconry a life-long commitment.

Trending

“I’ve just always been fascinated by birds of prey, even at a young age,” Pickens said. “I actually checked with Texas Parks and Wildlife about being a falconer years ago. It was very difficult before the age of the Internet.”

He added, “What fascinates me the most is that I can turn him loose and he will fly off and I can get him back. I’ve done that for 13 years now with this bird.”

Pickens has a special connection to his falcon, but he’s not considered a pet.

“He’s not a pet. He’s a hunting partner,” Pickens said. “After 13 years, he’s more like a family member. He’s as old as my grandkids.”

But even with his fondness toward the bird, Phoenix isn’t necessarily faithful.

“They never have a loyalty to you,” Pickens said. “His only tie to me is that I help him get something to eat.”

Falconry is considered a noble sport and has been dubbed the “sport of kings.” Often interchanged with the term hawking, it is ancient, dating back about 4,000 years.

The sport gained popularity in the United States by the 1930s, according to the North American Falconers Association. However, it’s a small club, with only about 4,000 licensed falconers in the U.S. Pickens counted about seven in the Tyler area.

Bradley Clark, a Smith County game warden, said the office sometimes gets calls from people wanting information on the sport. But from his experience, falconry isn’t exactly thriving in East Texas.

“It’s not dying, and it’s not an increase in any kind of trends,” he said. “It’s just a less-known way of hunting in East Texas.”

Pickens, who is also the director of missions at Smith Baptist Association, became licensed in 1987 and has owned eight birds throughout the years. He has been active in the Texas Hawking Association, where he served as president, vice president and editor. He also joined the North American Falconer’s Association.

Falconry is highly regulated. This includes inspection of equipment and facilities and submitting an annual report. It’s a complicated process intended to protect the bird.

Pickens said falconry is perhaps exclusive because of the tight regulations and ongoing care of the birds.

“You can go out and shoot a duck a lot easier than you can train a bird to catch a duck,” he said. “When you have a bird of prey, it’s a constant, 24-hour watching and caring.”

To become a falconer, individuals must apprentice for two years. With five years of experience, they are considered a general falconer before becoming a master falconer.

Pickens has participated in all types of hunting throughout his life, but he doesn’t prefer shooting animals these days.

“I’m just participating in nature,” he said. “This is my love and my obsession. I’m part of the game of life. I get to see what happens in nature everyday and I get to be a part of that. It’s a privilege to be a part of that. I like it enough that I don’t really care to do the other (kind of) hunting.”

During the season, Phoenix gets to hunt every morning except on Sunday. He flies into the air above a pond, and as his owner scares the ducks to make them fly, Phoenix swoops down quickly.

“Falcons have been scientifically clocked at over 225 mph in a dive,” Pickens said.

It’s all done by positive award. The bird is taught to come to the owner’s fist and to a lure for a food reward.

“For me, that’s true hunting,” Pickens said. “He’s been hunting. I’m not. I’m just helping him. I’m just along for the ride.”